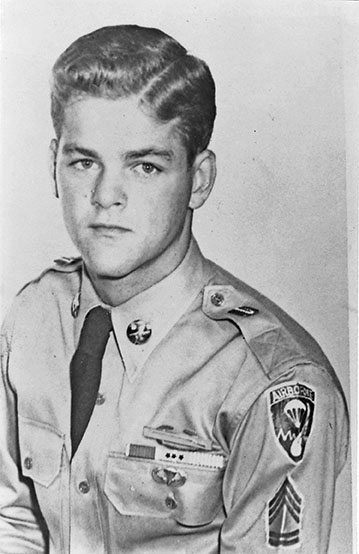

The term “hero” is thrown around very loosely. Professional athletes and fictional characters are given this title many times. Please don’t misunderstand, the point of this article is not to argue who is a hero and who is not. The beauty is probably in the eye of the beholder, in many cases. If a particular person receives motivation from a professional athlete or fictional character to motivate them or use their story to break free from their own personal tragedy, then being identified a hero may be in order. However, the Nonahood Interview for May highlights a man who is without a doubt the definition of a hero. A man whom several people have worked very hard to have the United States recognize as a hero. This month, we had the absolute honor of speaking to retired infantryman of the United States Army Robert Barfield, or “Boomerang Bob” as he is affectionately called. Bob lives close to the Wycliffe area of the Nonahood.

With the prior knowledge of the fact that you entered the service at a young age, can you please tell me a little about your childhood?

My parents broke up early and I didn’t live with either one of them (for) probably a year of my life. I was put in an orphanage and different homes. I was even in reform school for two years. It would happen, I was with a foster home and they owned a farm and they were losing money on the farm. My foster parents (were) real nice, I enjoyed the people. I only lived with them about a year and a half, and they decided to sell the farm. I went back under the court jurisdiction in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. You can imagine most people don’t want to hire a kid that’s 14. I wasn’t no kid. … I went back into the court, they were supposed to find me another foster home, they said. Instead, they sent me to this place called Kis-lyn Industrial School for Boys. You’ve read about this Dozier School here in Florida? Kis-lyn was as bad, if not worse, than that.

When did you begin service in the Army?

I joined when I was 17 years old from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1951. Right at the heart of the Korean War.

How long were you in the Army?

I also had four years in the Navy. … Three years in the Army and four in the Navy.

How did you make it to the Korean War?

After I went through basic training … it’s 16 weeks of infantry training. I went through jump school at Fort Benning, Georgia, as a paratrooper. As soon as I finished jump school, I got orders to go overseas. I was sent to an outfit called the Fifth Regimental Combat Team (5th RTC) … which was a regular infantry outfit. They had two regimental combat teams in Korea and I served with both of them….

What was your Korean War experience like at first?

In June the 23rd, I was a sniper. We had been hearing things for the last week, and I had heard something during the night, well towards the morning. It was in June, but it was really cold, way up in the mountains. I kept hearing something like somebody digging. My squad leader, obviously I was just a private then, he come up to my hole. He was checking on the men and he said, ‘Bob, you hear anything?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I think there’s something out in front of my position.’ I said, ‘Go ahead and sit here with me.’ He did, and sure enough it sounded like hitting the ground with a shovel. I looked over the barbed wire. The sun was just starting to come up. I figured now I could see if there was anything down there. I laid my rifle down by my knees. I looked over and just as I looked over I seen this orange flame. BAM! It knocked me right flat. The bullet hit me in the shoulder. The guys heard it, and my squad leader come running up to me and he stuck a couple bandages on my shoulder. The hill was so high … we had a tram to take the wounded off the hill.

Wow! You were shot? How long did that keep you away from the fighting?

After I got out of the hospital, they said I was unfit for front-line duty. There wasn’t a darn thing wrong with me. … I spent about 6 months … there were three of us. We decided we wanted to go back to Korea, to the front line. The way it worked in Korea, if you had 36 points you could rotate home. You’d get four points a month for front-line duty, then so far back (away from the front line), you’d get three points a month, then clear back to Japan you’d get two points a month. We decided we’d be there forever if we had to stay in Japan. All three of us decided to put in a transfer at the same time. I wrote, ‘I feel the Army, as well as myself, will benefit, especially if I’m utilized in a front line division.’ I got my transfer just like that.

Where did you go after you received notification of the transfer?

They sent us to the 3rd Infantry Division. This is the 3rd Infantry Division, and we were on a hill called The Boomerang, like the name implies, it was shaped like a boomerang. … The Chinese had (an) advantage. They could see down on us in 3 positions (from) the rear slope. There wasn’t that much going on at first; they would start throwing artillery at us, you know, and they have a thing called the bracket method. … They throw one round, maybe it hits above the trench. The next one would usually be in front of the trench, and look out for that third one.

When was the fighting the heaviest?

At the beginning of June (1953), they were bracketing our hill. … We had word that they intercepted … a telephone message that the Chinese were going to hit us on the 14th (Flag Day). Of course, we had heard this a few times before but nothing ever materialized. I was a squad leader then … 18 years old, had 5 stripes. My company commander called all the squad leaders to his bunker and told us to pass out to each man a double basic load of ammunition, that’s grenades and ammunition, (to) make sure everybody was on the alert. … Everything was quiet that day, every once in a while they’d throw a round at the hill. About 9:30 at night, just like that, it went into hell. They threw 17,500 rounds of artillery and mortar, plus used tanks. This was artillery, mortar, and tanks against our hill. They were hitting front, back, behind, on top, and every time a round would hit on top of my bunker, it would suck the air out of bunker. It was the craziest feeling.

When the artillery rounds decreased, the Chinese soldiers charged the U.S. at Boomerang. Many details of the events that occurred next, Bob explained, can be read about in a book he wrote (co-authored by Captain Mark Musgrave and Dave Lapham) named Insufficient Evidence.

Chapter 50 of the book describes, “At one point I saw Chinese in the trench line to my right. The ROKs (Republic of Korea allied soldiers) had obviously retreated. I picked up a BAR (M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle) – can’t remember whose it was, but he was dead – and charged down the trench line, killing eight or 10 Chinese. They kept swarming into our positions, and fighting had deteriorated to hand-to-hand combat. I ran back and forth screaming at my guys, shooting every Chinese I came across. Several times just by sheer numbers, they forced us back, but just as quickly we waded into them and pushed them back.” (Insufficient Evidence, page 208)

During this battle, through his own heroics, Sgt. Robert Barfield personally saved many lives. In some instances, he carried wounded to a safe location while under attack, when others refused out of fear of their own lives. One soldier, Second Lieutenant Lewis Hotelling (retired as Major Hotelling), Boomerang Bob’s commanding officer, was saved by his direct action. From that day forward, Major Hotelling’s life’s dream was to see Barfield awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor (the highest medal of valor in combat).

Boomerang Bob was initially recommended for the Medal of Honor in 1953. Additionally, he received this recommendation on a number of other separate occasions since then. Due to technicalities difficult to understand, the government has denied these repeated requests by eyewitnesses despite their affidavits and written sworn statements validating Bob Barfield’s actions on June 14, 1953.

The entire detailed story from when Robert Barfield was an orphan child to the repeated attempts for the United States government to award him the Medal of Honor is in his book Insufficient Evidence. Additionally, much of Boomerang Bob’s story can be found at robertbarfield.com.