Many years ago, as I rambled alone on a July evening through the empty streets of Reykjavik, a single pedestrian, a drunk staggering helplessly on inebriated limbs, crossed my path. We smiled at one another. Gazing upon the coldly brilliant sun setting behind a crest of nearby mountains, I resumed my stroll and asked myself, “Where the heck is everyone?” This is Reykjavik, the capital city of a small country, but a genuine country nonetheless. Don’t all capital cities bustle? I then glanced at a clock upon a church steeple and saw the time was 11:45 p.m. Oh, right. The midnight sun had addled my internal clock. So that’s why it’s so brilliant and bright, but not a soul outdoors …

My wife, Elizabeth, and I had booked flights from Luxembourg to Washington, D.C., on Icelandair, attracted by that airline’s famously cheap fares, but also out of curiosity. Our fare offered a stopover in Reykjavik at no charge. In Iceland’s fabled twilight, we were told, you could read a newspaper outdoors at 3:00 a.m. (True, it turned out. We tested.) But our stay was much too short and confined to the capital city. Beyond that newspaper-reading experiment, our main stopover accomplishments were to marvel at the astronomical prices of restaurant food, nearly all imported, and the Althing, the world’s oldest parliament, founded in 930. Otherwise, we learned little about Iceland’s geography, heritage or culture. So, the discovery that one of the streets in our neighborhood’s new annex, Laureate Park South, honors Iceland’s greatest modern writer, Halldór Laxness, came as welcome news. Dipping into Laxness’s work, we figured, would provide a peek into the secrets of that perplexing northern nation.

Over his lifetime, Halldór Laxness produced an impressive stack of 60 books, mostly fiction. To research for this article, your correspondent managed to read just a sliver of this output. Two and a half novels, to be brutally precise. Nonetheless, this modest effort yielded a satisfying glimpse into Icelandic life of the past century and an appreciation of the skills of a major Nordic writer little known in this country.

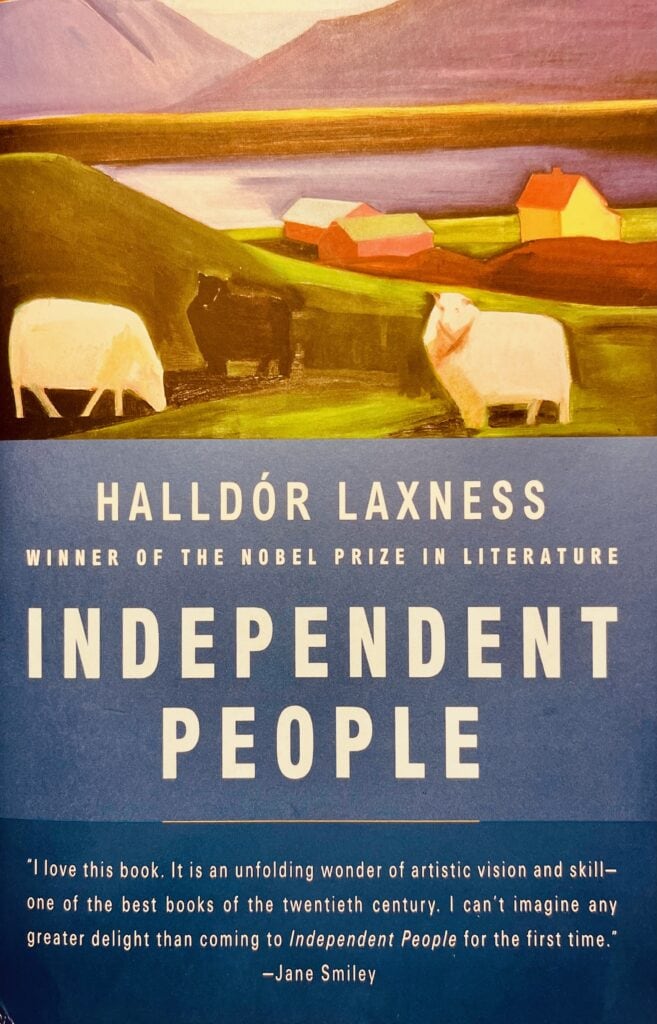

The Swedish Academy awarded Laxness the 1955 Nobel Prize for literature, ostensibly on the basis of a single novel, the imposing epic, Independent People. The right place to start, we thought, to learn a bit about Laxness and the culture of his native island.

A more fitting English title for this novel might be An Independent Man, for the narrative focuses not upon a race of people but on a single sheep farmer named Bjartur of Summerhouses, the most stubborn, single-minded – and, in many ways, unlikeable – character you are likely to encounter in fiction. But also unforgettable. Little seems to lighten the misery of Bjartur’s daily struggles to scratch out a precarious livelihood for himself and his kin. As we meet Bjartur, he has just purchased a dilapidated turf farmstead from the local bailiff, a sort of local magnate, for whom he labored 18 years as a shepherd. Bjartur is also about to wed. His farm, set upon a marshy moor girdled by low mountains, is said to be cursed by the ghosts of an Irish monk, Kollumkilli, and the vile witch Gunnvor. But that land and that farm are all that matters to Bjartur. They are the sole guarantee of his coveted “independence.” The pursuit of that independence, though, exacts a terrible toll: a life of grinding poverty.

Soon after escorting his superstitious bride, Rosa, to the farmstead, Bjartur learns she is pregnant with the child of the bailiff’s son. The secluded turf house is primitive. The second-story living space is supplied with a stove, bed and table, but no chairs. Downstairs, a barn. Meals are porridge and fish, but never meat. For most of the year, tending the sheep and raking hay require 18-hour workdays with one brief break for a meager lunch. As winter approaches, Bjartur decides to attend a local sheep roundup, leaving a gimmer, a young lamb, to keep his bride company. But Rosa, raised in comparative luxury in town, is starving. In her desperation, she slays the lamb she believes bewitched and consumes the carcass. No trace of the animal remains.

Arriving home, Bjartur guesses that the gimmer has wandered from the farm and launches a days-long search for her, again leaving Rosa, now approaching childbirth, alone on the farm. The episode that follows must be one of the most astonishing passages in modern literature. On the second day of his search, Bjartur eyes a bull reindeer grazing along the frigid Glacier River and devises a plan to capture the reindeer with his bare hands and lead him home. In his struggle to tame the reindeer, Bjartur hops onto the animal’s back, but the confused bull, trying to shake off his unwelcome passenger, dives into the icy river. As the rushing current carries the pair downstream at a furious pace, Bjartur saves himself by leaping onto an ice floe, and with uncommon strength manages to climb out of the water. Facing an oncoming blizzard, Bjartur now stands on the farther bank of an uncrossable river, with no shelter in sight. His only choice is to make his way across a barren landscape to some sort of settlement. Utterly soaked, fearing frostbite, he keeps moving, reciting stanzas of Icelandic sagas to distract him from the cold. Twenty-four hours later, a housewife, awakened by hammering outside, opens the door, and a creature resembling a human being tumbles forth. Revived, Bjartur chokes out that he had only taken “a stroll along the heights” searching for his lost lamb. The independent man offers no explanation for how he crossed Glacier River.

But his troubles are hardly over. When Bjartur returns home, he finds Rosa lifeless on the kitchen table. Before dying, she had given birth to an infant girl who had miraculously survived for days cuddled in the furry warmth of the family dog. That evening, Bjartur heads to town to visit the bailiff and his wife. He reluctantly intends to seek help for a funeral and secure a nursemaid but at first can only mumble that what he has to tell them “is nothing important.” After repeated questioning, Bjartur finally blurts out a riddle from his own verse that ends with the line “fallen the one rose.” Slowly deciphering this bizarre announcement of Rose’s passing, the bailiff and his wife gape at their visitor.

At this point, we are barely past page 100 of a 500-page epic! In the ensuing narrative, Bjartur raises, and mostly loses, a second family, and struggles vainly to raise sheep in Iceland’s unyielding climate. The theme of the physical and psychic cost of “independence” dominates this story, and one wonders if at times whether Laxness chooses to mock his protagonist or aims more directly to portray the cruelness of a brutal economic system keeping small Icelandic landholders consigned to lifelong misery. Some consider Independent People a masterpiece of fiction. Opinions may differ on that point, but this is clearly a masterfully written novel deserving of serious attention by all fans of literature, particularly those curious about Iceland of the early 20th century.

Halldór Guðjónsson was born in Reykjavik in 1902. In his youth, he wrote incessantly. At age 17, after publishing his first novel, Halldór, having adopted Laxness for his last name to honor his family’s farm, sailed to Copenhagen, which served as a stepping stone for extensive travels throughout Europe. In his early twenties, Laxness entered a Benedictine monastery in Luxembourg, which he abandoned, however, shortly before taking his final vows. In a 180-degree turn, he moved in 1927 to Los Angeles to pursue a career as a Hollywood screenwriter. Those career aspirations went nowhere, though, as Laxness fell out with movie moguls over a screenplay based on one of his novels. Laxness wanted a film set in Iceland starring Greta Garbo; the moguls favored Kentucky.

By this time, Laxness was drawing decidedly toward a version of socialism reflected in the realist novels of Theodore Dreiser, Sinclair Lewis and Upton Sinclair, all of whom he greatly admired. The October 1929 stock market crash cemented Laxness’s tilt toward socialism, and in the 1930s he produced his greatest literary efforts, including Independent People, works shaded by his political views. That decade also brought Laxness to the Soviet Union twice. On his second visit, Laxness, in a mystifying episode, witnessed Stalin’s pitiless show trials in Moscow, then returned home to pen a bland travelog based on that trip. This and other incidents eventually attracted the attention of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. In the late 1940s, Laxness was blacklisted, and his novels, which had known popularity among American readers, disappeared from bookshelves in the United States until 1997, a year before Laxness’s death, when Vintage Books republished Independent People. Further novels, such as the slyly amusing The Fish Can Sing and Laxness’s weird but barely readable experiment with modernist prose, Under the Glacier, have since been released by Vintage Books.

So, in the end, our chance discovery of Halldór Laxness has left us grateful. Grateful that a modest street sign recently erected in our new neighborhood has inspired us to read at least a sampling of Laxness’s literary output. And grateful that the American public has again begun to read the work of a major writer lost to us for nearly a half-century.