This is the 23rd in a series of articles that celebrates the lives of the Nobel Prize laureates whose names grace the 130+ streets of Laureate Park. These laureates are extraordinary individuals who through their lifetime achievements have made our daily lives immeasurably richer, often in ways not readily apparent.

Standing on a sidewalk on a bright December morning in Bern, Switzerland, I examined the medical order my doctor had scribbled out in German. My back ached terribly following a frigid evening of ice skating at the local Eisstadion Allmend, where I had made several turns around the rink carrying my one-year-old daughter in my arms. Relief would be nigh, the doctor assured me, once he had examined my Roentgen. Submitting to a Roentgen exam, whatever that was, hardly sounded appealing. If the procedure in question involved some sort of radiography, then why didn’t the doctor say so?

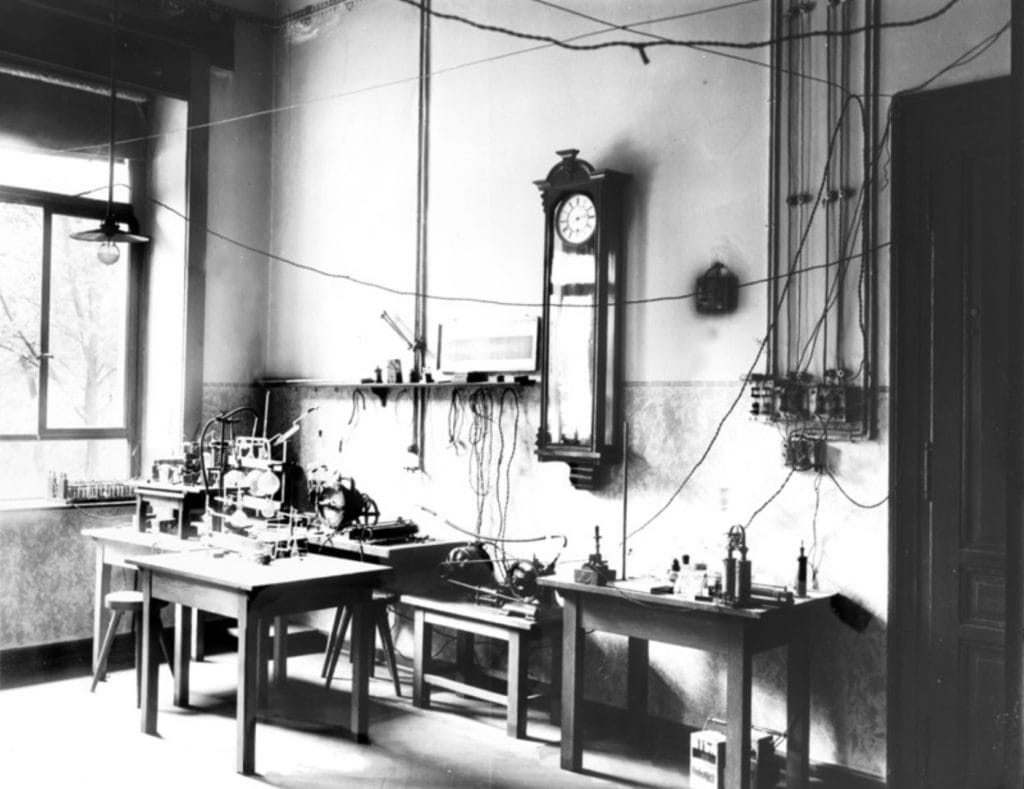

One evening in November 1895, University of Würzberg professor Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen fiddled in his laboratory with a device called a Crookes tube, a crude precursor of the cathode ray tubes omnipresent, until recently, in televisions and desktop computers. This apparatus, invented two decades earlier by Englishman William Crookes, consisted of a glass tube containing a partial vacuum. At each end of the tube were installed electrodes. As electricity was applied to one of the electrodes, a stream of “cathode rays” flowed through the tube that were collected by the electrode at the far end. The precise nature of these “cathode rays,” however, remained unknown. Observations had shown that Crookes tubes could produce occasional incidences of faint fluorescence outside the glass. But no scientist had yet applied serious study to these mysterious rays.

Employing a bit of lateral thinking, Roentgen hit upon the idea of encasing the Crookes tube in a black cardboard box to allow no light to escape the device. He then darkened the room, amped up the electrical current, and watched. By chance, in the corner of his eye, he noticed a faint glimmer of fluorescence flickering on a screen nine feet away that had been coated with the chemical barium platinocyanide. Cathode rays, he knew, could not travel that far. Am I observing a new kind of ray, he wondered, an unknown ray, an X-ray?

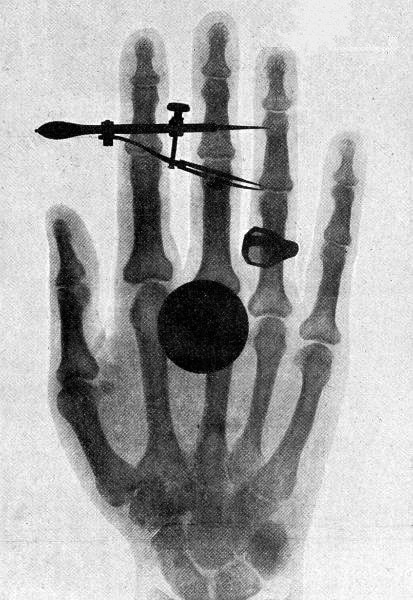

For the next several weeks, Roentgen enveloped himself in the loneliness of his laboratory, shut out all visitors including his wife, Bertha, and manically observed the effects of these curious rays. He held various objects before his fluorescent screen – metal, paper, wood, glass – and was profoundly shocked, at one point, to discover a clear outline of the bones of his hand with just a faint suggestion of the surrounding flesh. Finally, on December 27, Roentgen admitted Bertha to his lab and snapped the first recorded human X-ray, an exposure of her hand, which clearly showed the outline of her wedding ring on one finger. The following day, Roentgen delivered his first of only three papers on his discovery that he produced in his lifetime, a document entitled “On a New Kind of Rays.” On New Year’s Day, he mailed copies of the paper to fellow scientists in an attempt to dampen the inevitable sensationalism arising from his discovery.

Unlike the fast-paced life of our present day, we are often inclined to regard the 1800s as a century stuck in slow motion. But Roentgen’s discovery of X-rays instantly ignited a firestorm of intense interest. Within two weeks after announcing his discovery, he was summoned to the Berlin court of Emperor Wilhelm II, to whom he demonstrated his findings. Within a year, X-ray devices were being used in Europe and the U.S. to locate bullets, bone fractures, kidney stones, and swallowed objects within human bodies. Thomas Edison and his associates, jumping into the fray, initiated experiments with alternative chemicals to improve upon the barium platinocyanide employed by Roentgen. But when one of those associates, 39-year-old Clarence Dalley, lost his life to radiation poisoning acquired during those experiments – the world’s first such death – Edison dropped his work on X-rays. An understanding of the dangerous side effects of exposure to X-rays was slowly emerging.

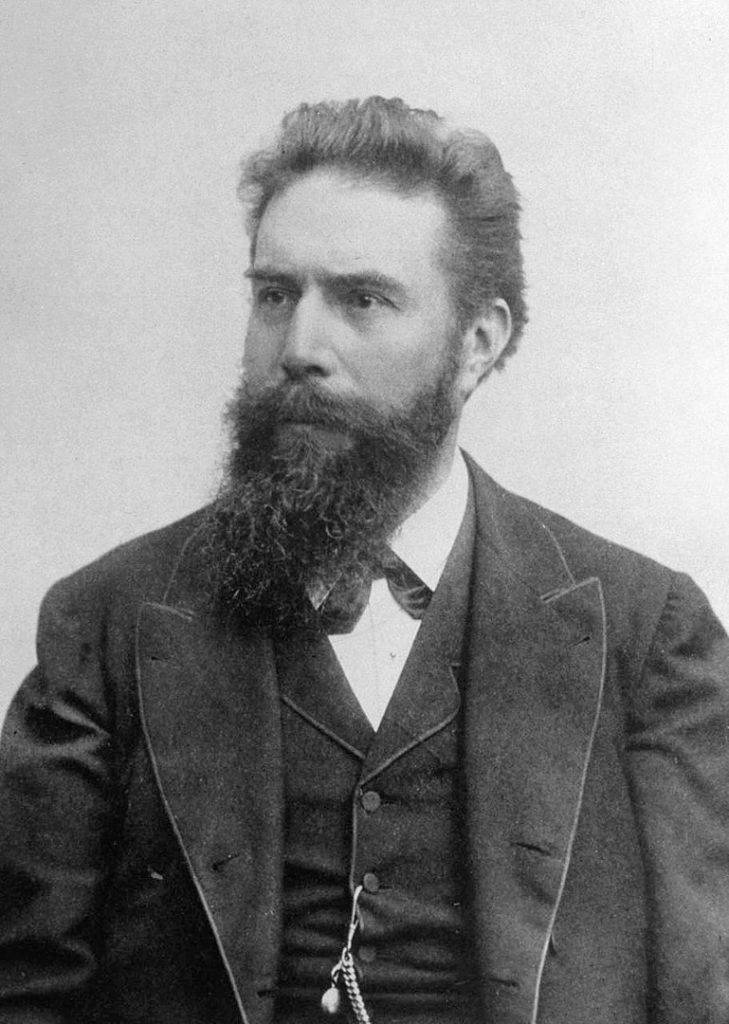

The educational trajectories of Nobel laureates generally track a predictable path, from primary school to the conferral of a hard-earned Ph.D. or two. In contrast, Wilhelm Roentgen’s academic career zigzagged. The obstacles he overcame would have broken a man of lesser determination. In his secondary school in Holland, Roentgen, unfairly accused of producing an unflattering caricature of a teacher, was summarily expelled. When his lack of academic credentials denied him entry to the University of Utrecht, Roentgen discovered he could pursue his studies by passing an exam for entry to the Swiss Federal Polytechnic Institute in Zurich, where he obtained his Ph.D. in physics in 1869. Roentgen’s initial efforts to obtain a professorship failed, but he finally managed to secure a position as lecturer in Strasbourg. Later appointments brought him professorships in Hohenheim, Giessen, Würzburg and Munich.

We know of two accepted spellings for Wilhelm’s family name, Röntgen and Roentgen. The double dots above the letter “o” in the first of these, the German spelling, produce an umlaut, which in English is normally replaced with the “oe” diphthong. Except, of course, at The New Yorker magazine, where superfluous umlauts – or more precisely, diaereses – adorn such words as “coöperation.” Lake Nona, though, has devised its own unabashedly unauthorized spelling of that family name as reflected in the local street sign that reads “Rontgen Circle.” In our neighborhood, we of course would never condone dalliance on the wrong side of the law, but if one or two residents of Rontgen Circle were to surreptitiously affix two small circles above the “o” on their street sign, we would be inclined to look the other way. No matter, though. Since his death in 1923, Roentgen’s surname has been attached to objects and phenomena of various descriptions. For example, the abbreviation REM (no, not the 1980s rock band) stands for Roentgen Equivalent Man, a measurement to gauge the health effects of ionizing radiation on the human body. And Roentgen remains one of an octet of Nobel laureates after whom an element has been named, in his case the short-lived synthetic element 111, Roentgenium. Even more exciting – for some of us, anyway – a type of tulip also bears his name.

In the 125+ years since Roentgen’s extraordinary discovery, X-rays have evolved to spawn such technological advances as computerized tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and echocardiography. The countless dentist offices that crowd our neighborhood are all amply supplied with a modern version of the apparatus initially invented by Wilhelm Roentgen. For someone who contributed so much to our physical (and dental) wellbeing, shouldn’t the name Roentgen be better known in this country? Especially in a town that harbors a Medical City? Wilhelm Roentgen, though awarded the first Nobel Prize in physics in 1901, did not initially know what the rays he discovered actually were, so he called them X-rays, the X to indicate “unknown.” We now know a lot about X-rays, but we nevertheless retain a label for them that recalls our former ignorance. Perhaps our German-speaking friends across the Atlantic have gotten it right, calling the exam that employs the rays Roentgen discovered by a more appropriate name. That is, of course, a Roentgen exam.

Photos Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons