Just one question pops up on our Medical City quiz today: Can you name one scientist, any scientist, responsible for inventing the COVID vaccine? Sorry, Anthony Fauci and Deborah Birx don’t count; though they led the national effort to convince (most of) us to take the vaccine, they didn’t develop the vaccine themselves. Isn’t it odd – and revealing – that a couple hundred million of us were jabbed with a concoction produced by Pfizer, Moderna or Johnson & Johnson, yet we struggle to call to mind any scientist’s name to attach to those life-saving spritzers?

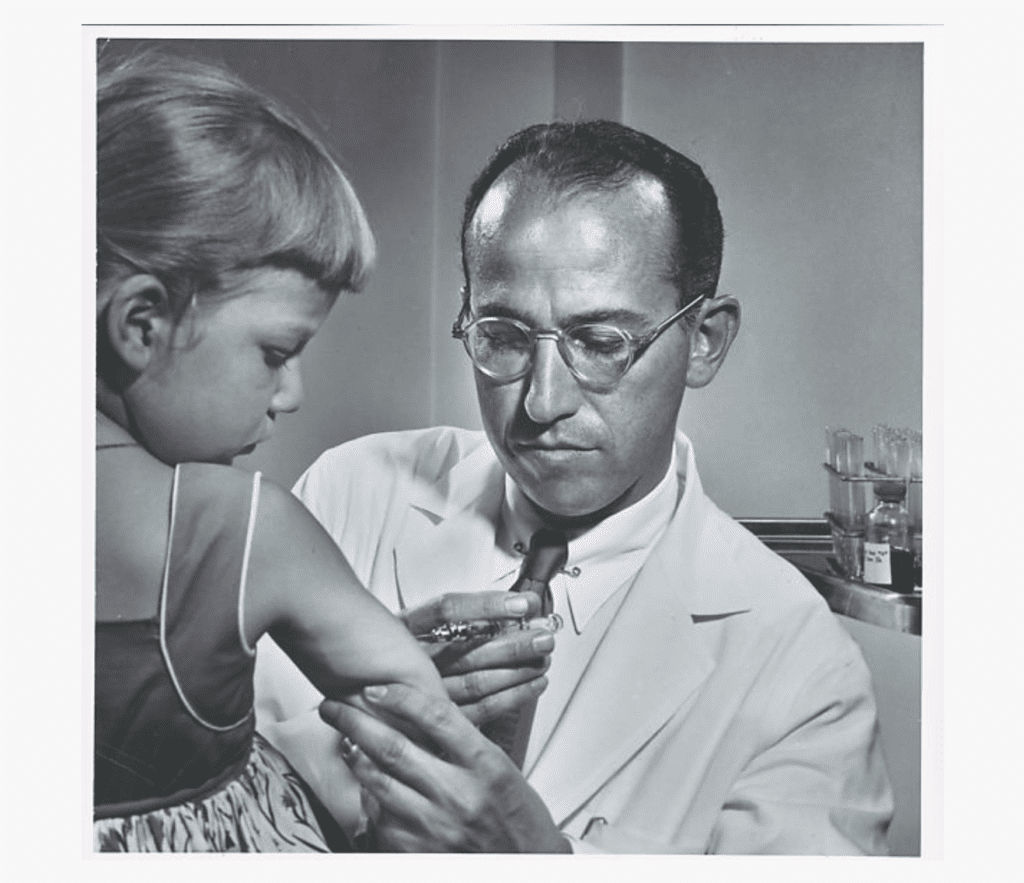

Things were different in the 1950s. A second hypothetical question on our Medical City quiz would ask you to name a scientist associated with the polio vaccine. For most of us, especially boomers born that decade, that question is easy: We effortlessly recall the name of Jonas Salk. Older boomers further recall, in some cases quite vividly, the terror that polio epidemics visited upon the homes of American families with small children in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The need for a vaccine to protect children from those scourges had acquired alarming urgency.

Though recognized since ancient times, polio, or poliomyelitis, was an uncommon affliction until the early 20th century, when an outbreak in New York City in 1916 unexpectedly caused 10,000 cases of the disease and over 2,000 deaths. Severe cases were terminal; serious cases left children paralyzed or crippled for life. Outbreaks of varying intensity came and went worldwide in the following years. In 1921, a rising politician named Franklin Roosevelt contracted the virus following an ocean swim near Campobello Island, on the sound separating eastern Maine and New Brunswick. He never walked again unaided. But the illness of the man who would be elected president and lead our country through the Great Depression and World War II did bring forth one positive consequence, which was the establishment, in 1928, of a spa in Warm Springs, Georgia, for the care of children suffering from polio (and for FDR’s personal use).

At first, Warm Springs struggled financially, as the young visitors to the spa paid – or didn’t pay – for their treatments according to their family’s income. To keep the operation afloat, Roosevelt’s law firm partner and confidante, Basil O’Connor, hit upon the idea of organizing “Birthday Balls” in FDR’s honor to attract charitable donations for the fight against polio. Americans nationwide emptied their pockets to attend the balls, which collected funds not only to support Warm Springs but also wider public health campaigns. From these Birthday Balls emerged the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, an organization that from its founding in 1937 would play a major role in the development of a polio vaccine. (Soon after, the foundation launched the March of Dimes campaign. Again, those of us of a certain age remember the miniature March of Dimes cardboard displays in our neighborhood drugstores, into which the thin 10-cent coins, supplied with FDR’s profile, were carefully inserted.)

Enter Jonas Salk, the progeny of unschooled Russian-Jewish immigrants headed to New York City at the turn of the last century who brought to their adopted country a rock solid faith in the value of education. During the 1916 polio epidemic, as Jonas turned two, Mrs. Salk, together with her Upper West Side neighbors, lived in fear that one of the dreaded black sedans conveying public health officers might arrive at her doorstep to remove her son to a local, but for her unreachable, quarantine station. Public health measures in those days were no joke. Luckily, the infant Jonas escaped the disease.

Armed with rare intelligence and exceptional intellectual drive, Jonas Salk grew naturally into a highly bookish student. After securing a B.A. in chemistry from the City College of New York and an M.D. degree from New York University in the late 1930s, Salk turned his attention to medical research, specifically the study of bacteriology. Salk later explained that by pursuing such research, rather than the practice of medicine, he could serve mankind as a whole rather than tend to single patients. In 1941, Salk’s postgraduate work led him to collaborate with one of his mentors, Dr. Thomas Francis, then considered the nation’s preeminent virologist. Salk’s work with Francis, first at New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital and later at the University of Michigan, produced an unexpected result the following year. As World War II rolled in, the Pentagon had sought out Dr. Francis to develop a flu vaccine to protect the millions of soldiers suddenly swelling the ranks of the U.S. military. In New York and Michigan, Francis and Salk had experimented with a prototype of a vaccine containing flu viruses killed in a bath of formalin (basically the liquid version of formaldehyde). The dead viruses, injected into volunteer soldiers, they observed, stimulated the antibodies needed to fight the flu virus. The pair had invented the world’s first flu vaccine, the basic structure of which remains in use today.

In 1947, anxious to manage his own medical laboratory, Salk accepted a position to direct a research lab at the University of Pittsburgh. The lab’s installations were paltry, so Salk turned to Basil O’Connor and the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis for help. Funding began flowing in Salk’s direction, coupled, however, with an insistent demand to develop a polio vaccine. Working tirelessly, Salk and his Pittsburgh team by 1952 produced a working version of a killed virus vaccine tested on scores of children housed in two state institutions in Western Pennsylvania. That same year, in a singularly courageous move, Salk injected his sons with the still-experimental vaccine.

Americans, meanwhile, were devouring every scrap of news about work on the polio vaccine and were growing impatient. Some media reports suggested that the vaccine, though fully developed, was being withheld from the public. To calm the nation’s nerves, Basil O’Connor came again to the rescue. His brainstorm was to have Salk speak on national radio to explain the timelines for production of the vaccine. On March 26, 1953, Salk did so, reassuring his nationwide audience that results of recent experiments to test the efficacy and safety of the vaccine provided “justification for optimism.” This address not only helped to quiet anxieties about the imminence of a vaccine but also made Jonas Salk an instant, if reluctant, celebrity, a status that irked many of his fellow scientists. Not least among these was noted virologist Albert Sabin, who mocked killed virus vaccines as ineffective and even belittled Salk as a “mere kitchen chemist.” Nonetheless, 1954 saw over 400,000 children inoculated with Salk’s vaccine, and the following year, after careful evaluation by an impartial team led by Michigan’s Dr. Francis, the Salk vaccine was declared safe and effective for use by the public. In one sense, however, Albert Sabin won out in the end as the vaccine he developed based on live viruses – a liquid that many of us recall imbibing in tiny paper cups in primary school – eventually replaced Salk’s vaccine in the early 1960s.

Later in life, Salk founded the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego, California, which today conducts research into a range of diseases, including HIV and Alzheimer’s. To the end of his days, Salk remained uncomfortable with the fame he had acquired in the development of the polio vaccine and continued to shun celebrity.

We personally know only one family residing on Salk Way, native Marylanders Scott and Jamie Windell, whose home is undoubtedly the most striking edifice on that street. The term “edifice” may seem overdrawn, but the Windell residence has a mid-century flair that calls to mind the work of such 20th-century architectural giants as Alvar Aalto, Philip Johnson and Richard Neutra. Jonas Salk himself might have felt at home in such a house. Scott and Jamie have assured us, by the way, that they are fully vaccinated and boosted. So, we can only expect that the residents of the street honoring Jonas Salk – within Orlando’s Medical City – must also have done so and thus paid homage, however unconsciously, to one of history’s most celebrated medical researchers and vaccine inventors. Celebrated, that is, across the globe, except at the Royal Swedish Academy, which failed to honor Jonas Salk with a Nobel Prize. But no matter. We Laureate Park residents, having recently emerged from a pandemic equal in horror to the polio scourges of the last century, will long regard the shy Dr. Salk with special reverence, just as we are grateful to the nameless thousands who labor in labs today to manufacture the vaccines needed to quell 21st-century illnesses.

Those interested in learning more about Jonas Salk might dip into a compelling read entitled Splendid Solution by Jeffrey Kluger. Recently, we noticed on the web that a film based on the book starring Jeremy Strong will be forthcoming soon.