One cloudless day in 1915, a load of dynamite destroyed the central piers of a stone bridge that had stood untouched for centuries next to the mainly Muslim town of Višegrad in Bosnia. The bridge, named for Mehmed Paša Sokolović, the Ottoman Grand Vizier who had ordered its construction, spanned the River Drina not far from Bosnia’s current border with Serbia. The previous year, a Serbian teenager named Gavrilo Princip had sparked World War I with his assassination of the heir to the Austrian-Hungarian throne, Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo, Bosnia’s principal city. Earlier, Bosnia had been attached to the Austria-Hungarian Empire. Though Princip was Bosnian (or Bosniak), Austria blamed Serbia for the murder and declared war against that nation, a move that led major European powers to activate their regional alliances. When the dust had settled, Britain, France and Russia were squared off against Germany, Austria and the Ottoman Empire, with lesser powers choosing sides. In the four following years, the Great War brought destruction and death to Europe, Africa and the Middle East, as well as to the quiet town of Višegrad and its famous bridge.

Whew! In so few words, a lot of information to unpack. Questions jump to mind. For a start, what and where is Bosnia? And if Bosnia is in Europe, why are so many Bosnians Muslim? What is a Grand Vizier, and why is Mehmed Paša Sokolović’s name part Turkish and part Slavic? And what does any of this have to do with the winner of the 1961 Nobel laureate for literature, Ivo Andrić?

Let’s begin with Bosnia. As a component of former Yugoslavia, Bosnia is today bordered by Croatia to the north and west, Serbia to the east, and Montenegro to the south. (The nation’s full name is Bosnia and Herzegovina, but we’ll use the shorter name for this article.) Some consider Bosnia, which declared its independence in 1992 from Yugoslavia, the most complex political entity on earth. It is here where three major religions – Orthodox Christendom, Roman Catholicism, and Islam – converge and collide, generating tensions that have endured the centuries. Today, one-half of Bosnia’s citizenry is Muslim, while Roman Catholic Croats count for 30% of the population, and Orthodox Serbs 15%. Bosnia currently maintains three (!) presidents, each of whom represents one of these demographic groups. These presidents, however, have limited authority, as real power rests with the prime minister and the legislature. A volatile cocktail for political strife and disruption, if there ever was one.

These complicated constitutional arrangements stem directly from Bosnia’s exceedingly complex history. The first race to conquer the region were the Illyrians, who were partially dislodged by Celts, then entirely overrun by the Romans. The Huns arrived in 455, only to be evicted a century later during Constantinople’s reconquest of the region. Meanwhile, Southern Slavs filtered in from the east, weakening Constantinople’s hold and ushering in several centuries of murky Dark Ages chaos. By the turn of the millennium, both Rome and Constantinople, the centers of Catholicism and Orthodox, had begun to dispatch missionaries to convert pagan populations throughout Eastern Europe. The Croats turned to Rome, the Serbs to Constantinople, while the Bosnians, who by the mid-12th century had forged an independent state, the Banate of Bosnia, established their own unique version of Christianity, the Bosnian Church. Eventually, this Church fell afoul of Rome, which viewed the denomination’s teachings as heresy. But efforts in the 13th century by a succession of popes to employ the Hungarian military to impose the Catholic faith onto Bosnian Christians failed miserably. Bosnian nobility repulsed the Hungarian interlopers and sustained their curious religion until 1463 when the Ottomans arrived. Truth be told, the Bosnian Church’s spiritual hold over its adherents was not strong. In this environment, Islam found fertile territory for converts, and many Bosnians, though Slavic-speaking, turned easily to that religion. The Ottoman Empire’s dominion over Bosnia was to last more than four centuries, until 1878. Fifteen years later, Bosnia’s greatest writer, Ivo Andrić, came into this world.

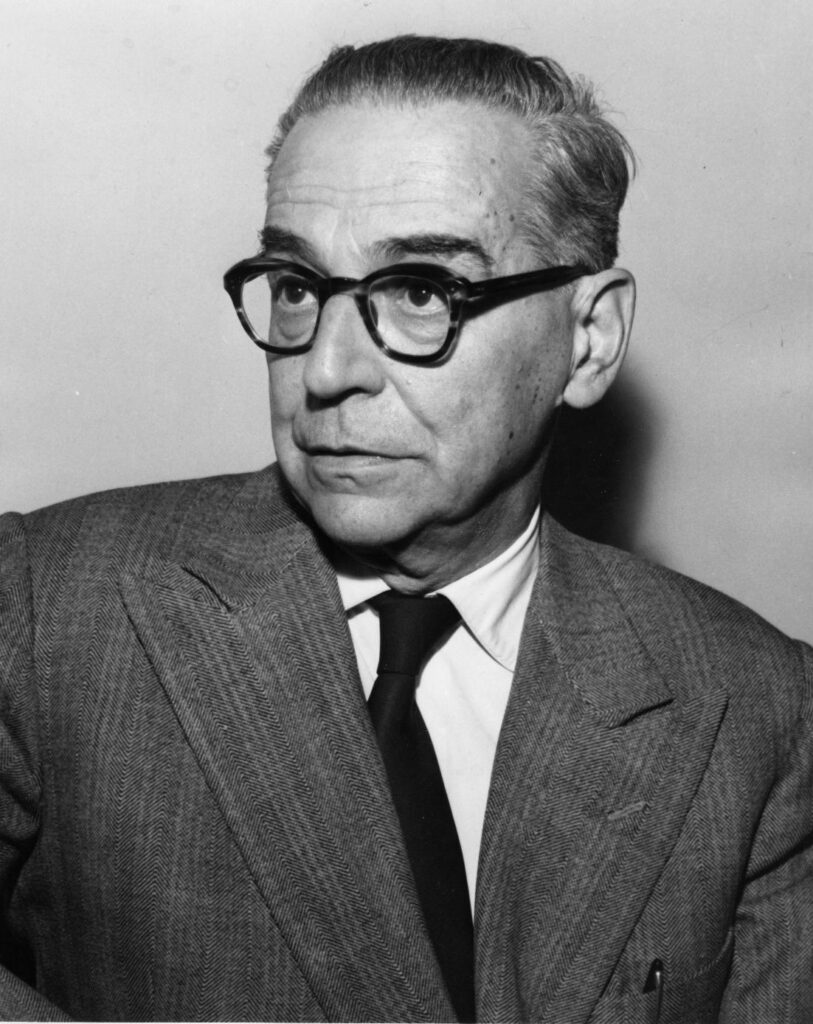

Ivo Andrić’s biography closely tracks the tempestuous history of the Balkans of the 20th century. Though born of ethnic Croat parents, Andrić as a youth developed strong sympathies for the ethnic Serbs who agitated against their Austria-Hungarian overlords. Still a high school student in Sarajevo, Andrić was elected president of the Serbo-Croat Progressive Movement, a secret society formed to carry on this struggle. One member of the society was Andrić’s close friend, Gavrilo Princip. The duties of president required Andrić to deliver public speeches condemning the Austrian-Hungarian regime, remarks that did not escape the attention of the imperial police. Over the next three years at universities in Zagreb, Vienna, and finally Krakow, Andrić kept up his political activism, but his energy flagged as he contracted tuberculosis, a condition to plague him for the rest of his life. When the news of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand in June 1914 reached Krakow, Andrić returned home in support of his fellow activists. A dangerous move, as he and several of his colleagues were soon arrested and dispatched to prison until July 1917 when Charles I, having ascended to the Austrian-Hungarian throne the previous year, announced a general amnesty for political prisoners.

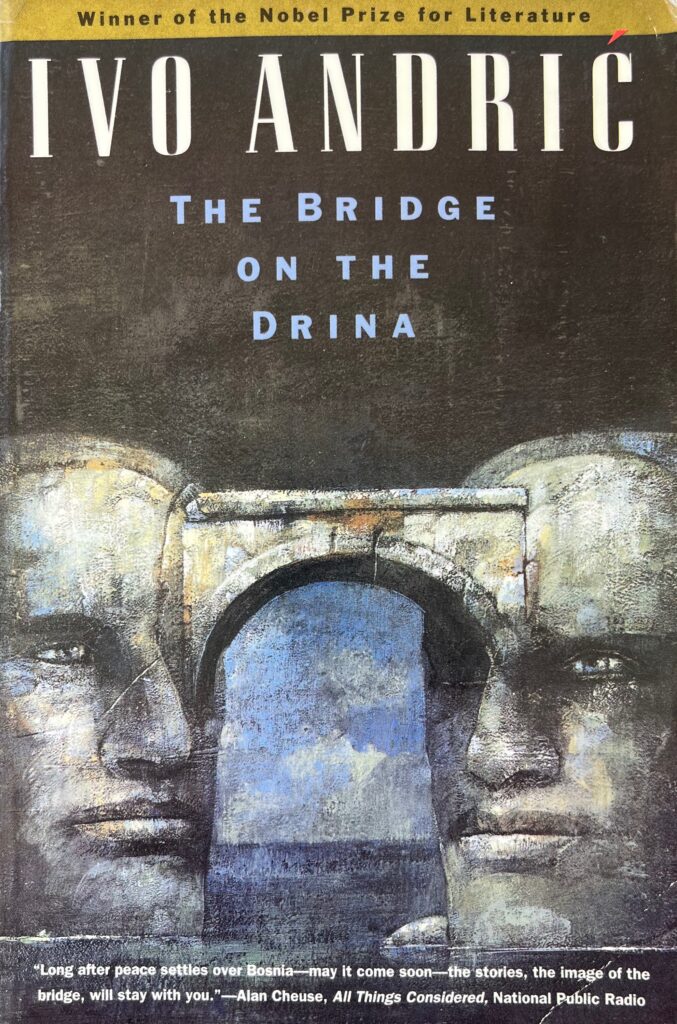

As World War I closed, Austro-Hungarian domination of the Balkans ended. A new state, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia), was formed, and Andrić, already an accomplished author and poet, applied to serve in the diplomatic service of the new nation. Over the next two decades, he enjoyed a distinguished diplomatic career, a line of work that afforded him ample spare time to produce a remarkable literary output. In 1939, Andrić attained the culmination – if not height – of his diplomatic profession when he was appointed Yugoslavia’s ambassador to Nazi Germany. Unsurprisingly, Andrić’s transactions with the Nazi regime were, let’s say, awkward. Following Germany’s 1941 invasion of the Balkans, Andrić was transported to Belgrade, where he was kept under house arrest for the duration of the war. The happy result of this confinement was to be a genuine literary masterpiece, a sprawling novel entitled The Bridge on the Drina.

Even in translation, the prose of this novel stuns and sparkles. On page 1, Andrić introduces the setting and focus of his narrative with these words: “Here, where the Drina flows with the whole force of its green and foaming waters from the apparently closed mass of the dark steep mountains, stands a clean-cut stone bridge with eleven wide sweeping arches. From this bridge spreads fanlike the whole rolling valley with the little oriental town of Višegrad and all its surroundings, with hamlets nestling in the folds of the hills, covered with meadows, pastures and plum orchards, and crisscrossed with walls and fences and dotted with shaws and occasional clumps of evergreens. Looking from a distance through the broad arches of the white bridge it seems as if one can see not only the green Drina, but all that fertile and cultivated countryside and the southern sky above.”

How did this bridge to Višegrad come to fruition? In the early 1500s, Turkish officials intending to fill the ranks of the Janissary, an elite corps guarding the life of the Sultan, kidnapped a Serbian youth named Sokullo near Višegrad and transported him to Istanbul. Sokullo, renamed Mehmed Paša Sokolović, not only survived, but in time rose through the Ottoman military and political ranks to attain the position of Grand Vizier, the Ottomans’ equivalent of prime minister, second in power to the Sultan himself. The aging Sokolović wished to present his native town with a gift of lasting value. Hence his order to build the bridge at Višegrad.

For Andrić, the Sokolović Bridge is an elegant stage upon which pass the lives of a diverse population – Muslims, Croats, Serbs and Jews – from its completion in the late 1500s to that sudden blast during World War I. Some events recorded in Andrić’s novel are grotesque and tragic, such as the fate of a Serbian workman who, during the bridge’s construction, is fingered as an agitator and impaled upon the span, in a gruesome warning to others. Or the Muslim bride who flings herself into the Drina rather than marry a Christian groom. Other events are bittersweet, even hopeful. When floodwaters nearly washed away the bridge along with the lower sections of Višegrad, townspeople of different faiths huddled together on the bridge’s balcony, the kapia, in relative peace. Some readers see the bridge as a symbolic link between East and West. Others contend that Andrić, in his writing, favors the Serbs and Croats over Višegrad’s Muslims. I detect no such bias, though, nor can I find symbolism of any kind to attach to the bridge. But who knows? In the end, what counts is that through Andrić’s narrative, we are privileged to gain an introduction not only to the history and culture of Bosnia and Herzegovina but also to that of the Balkan region, the Ottomans, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. History about which few of us are knowledgeable. If for nothing else, that makes reading The Bridge on the Drina well worth your time and effort.

Postscript: After the 1915 blast, the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge was rebuilt in the 1920s, then destroyed once more during World War II and subsequently rebuilt. Today, the bridge is a UNESCO heritage site. Looking for Lake Nona’s Andric Lane? Just have a look at your receipt during your next visit to our local Lowe’s.