This is the 20th in a series of articles that celebrate the lives of the Nobel Prize laureates whose names grace the 130+ streets of Laureate Park. These laureates are extraordinary individuals who through their lifetime achievements have made our daily lives immeasurably richer, often in ways not readily evident.

A mere two meters separate Dufourspitze and Dunantspitze, the tallest summits in Switzerland, a nation chock-full of mountains of countless shapes and sizes. In Western Europe, only Mont Blanc tops those peaks in height. Our measuring tape shows the vertical reach of Dufourspitze at 4,634 meters (15,203 feet), an alp named after Guillaume-Henri Dufour, a Swiss general under Napoleon who later accomplished work of greater social good in collaboration with his posthumous neighbor, Henry Dunant of Geneva, whose summit checks in at 4,632 meters. These adjacent peaks fittingly honor two colleagues who cooperated closely in crafting organizations that vastly improved the wellbeing of citizenry and soldiery alike. But if the lofty heights of Dunantspitze aptly echo the start and finish of Henry Dunant’s productive life, his middle years were spent at much lower economic elevations. So low, in fact, that after having created the International Red Cross, the YMCA’s international branches, and the basic tenets of the Geneva Convention – among other achievements – Dunant for years slept on park benches in Paris and survived on scattered crusts of bread. Recognition of his contributions to the betterment of our daily lives, especially those of soldiers, came only decades later when he reemerged from abject obscurity in a small village in Switzerland to claim lasting international fame.

Henry Dunant’s pious Calvinist parents devoted much of their considerable Christian energies to helping the poor and downtrodden in the Geneva of the early 19th century, and their philanthropic zeal and organizational flair visibly shaped Dunant’s youth. In 1852, still in his early 20s, Dunant helped establish the Swiss branch of the YMCA, an organization founded eight years earlier in London by Sir George Williams, who wished to steer young men away from brothels and drinkeries. Soon after, Dunant worked to knit the national YMCAs into an international consortium. He was already making his mark on the world, but his dreams were big, as big as the world itself.

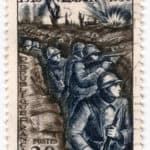

Having gained some modest experience as a fledgling banker in Geneva, Dunant launched into a business venture aimed at attracting Swiss settlers to the French colony of Algeria. The settlement at a place called Sétif soon encountered economic difficulties that threatened its continued existence. Dunant saw a possible solution to the settlement’s struggles by securing water and land rights from the French government. For Dunant, though, this meant no timid approach to local authorities. Instead, the audacious 31-year-old sought an audience with the emperor of France, Napoleon III, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, to secure those rights. At the time, Napoleon III was encamped in Northern Italy, leading troops of French and Sardinian troops against the armies of the young and militarily-inexperienced Franz Josef of Austria. At stake was the liberation of Italy from foreign interventions and the eventual reunification of that nation, a conflict known as the Second Italian War of Independence. (Yes, European history is complicated, but let’s put aside those geopolitical details for now.) Arriving at the French encampments on June 24, 1859, Dunant unwittingly bumbled upon one of Europe’s bloodiest struggles of the 19th century, the Battle of Solferino, a Sardo-French victory over the Austrians that left 18,000 soldiers dead in one day.

The scenes of the dead and dying on the field of battle traumatized Dunant. Distraught by the absence of medical care for the wounded, he organized transport and medical attention for the thousands of suffering soldiers, calling on local residents for aid and personally bankrolling needed supplies. Back home in Geneva, Dunant penned an account of his experience entitled Un Souvenir de Solferino (A Memory of Solferino) that he published with his own funds and shipped to leading political leaders throughout Europe. With superb narrative skill, Dunant in this slim volume described the progress of battle and awful agonies of the wounded and, more importantly, raised serious questions whether concerted efforts could better handle the transport and initial medical treatment for soldiers wounded in combat. With clear and cogent arguments that would leave only the most unfeeling reader unmoved, Dunant in so many words argued for the creation of an international organization to achieve these purposes.

Dunant never met Napoleon III at Solferino. But much like the public reaction in this country to the contemporaneous Uncle Tom’s Cabin, his account of the suffering of soldiers at Solferino resonated throughout Europe. The subsequent outcry led Dunant, General Dufour, and three others to establish the International Committee of the Red Cross in 1863, and one year later, corps of Red Cross medics appeared for the first time on a battlefield in Denmark, wearing red-upon-white armbands, a design inspired by the flag of Switzerland. And that same year, building on the success of the Red Cross, 12 European nations convened to sign a document championed by Dunant – the Geneva Convention, arguably one of the most important treaties in human history. The convention, which has been amended several times since its initial adoption, has influenced the behaviors of combatants in wars since. Soldiers treated at Lake Nona’s VA Hospital and similar facilities worldwide are grateful, I am sure, for the protections offered by the Geneva Convention.

Every superhero, as we know, contends with a super villain. The seemingly superhuman Henry Dunant faced his own nemesis in the person of Gustave Moynier, one of the five founders of the Red Cross. Among other issues, the pair quickly quarreled over Dunant’s insistence that the Red Cross should secure the principle of neutrality for wounded soldiers. Dunant won that debate when the concept was included as one of the basic tenets of the Geneva Convention. Meanwhile, though, his businesses foundered, forcing him into bankruptcy, and Moynier maneuvered to have his rival not only expelled from the Red Cross leadership but also blocked from earning financial assistance elsewhere. Years of a vagabond existence ensued as Dunant roamed penniless throughout Europe, finally settling at a hospice in the town of Heiden in the northeast corner of Switzerland.

Dunant’s remarkable resurrection evokes scenes from a fairy tale. In 1895, a Swiss journalist, having met Dunant by chance on a walk in Heiden, authored an article about his life that swiftly reprinted throughout Europe. The renewed interest in Dunant’s accomplishments caused European elites to rethink the history of the Red Cross, where up to then Dunant’s role had been minimized. His newfound fame eventually attracted the attention of the Swedish Academy, and in 1901, Dunant, together with French pacifist Frédéric Passy, earned that organization’s very first Nobel Peace Prize. True to his humanitarian nature, Dunant never accessed his prize money during his lifetime but rather allotted portions of the prize money to charity in his will.

If your travels ever bring you to Heiden, make sure to visit the Henry Dunant Museum, an installation housed in the former hospice where that exceptionally selfless laureate spent his final two decades. A good map of Switzerland will take you there. But just in case you were wondering: No matter how hard you look on that map, you will find no mountain peak called “Moynierspitze.”

Next month: César Milstein, Manufacturer of Monoclonal Antibodies