If you’ve ever viewed a play by Harold Pinter and found his characters to be creepy and weird, consider this: Pinter himself looked upon them as strangers. So, you say to yourself, if Pinter had such a dim appreciation of his own characters, then how am I supposed to understand them? Let alone identify with them?

Let’s be blunt. Pinter’s characters are not nice people. By the end of a Pinter play, they will remain strangers to you. You will learn little, if anything, about their past, about what motivates them, or even how they ended up on stage in the first place. These are not the kind of folks with whom you would gladly raise a glass at one of our local watering holes, such as at happy hour at Bosphorus Restaurant. But once viewed, you might not be able to get them out of your head. And despite yourself, you may eventually find them captivating, even entrancing.

Normally we attend the theater to be entertained. Comedies and musicals are popular, or works of drama with a beginning, middle and end. A plot that you can follow and understand. But Pinter has a different goal in mind for you. He wants to disturb you, shake you up, have you leave the theater unsettled and uncomfortable. He will slyly burrow into your psyche by sowing questions about communication, memory, dominance and submission. As the curtain falls, you might say to yourself, “What happened?” Though you will understand pieces of what happened, you will be unable to assemble those pieces into something resembling a coherent whole or clear message.

How does Pinter manage to create this unformed, dreamlike, often-hostile atmosphere that so frequently pervades his plays? Sure, it would be presumptuous for us to reduce Pinter’s approach toward drama to a set of facile devices. But since Pinter doesn’t seem to want us to understand his plays and takes what can only be described as an aggressive attitude toward his audience, let’s return the favor.

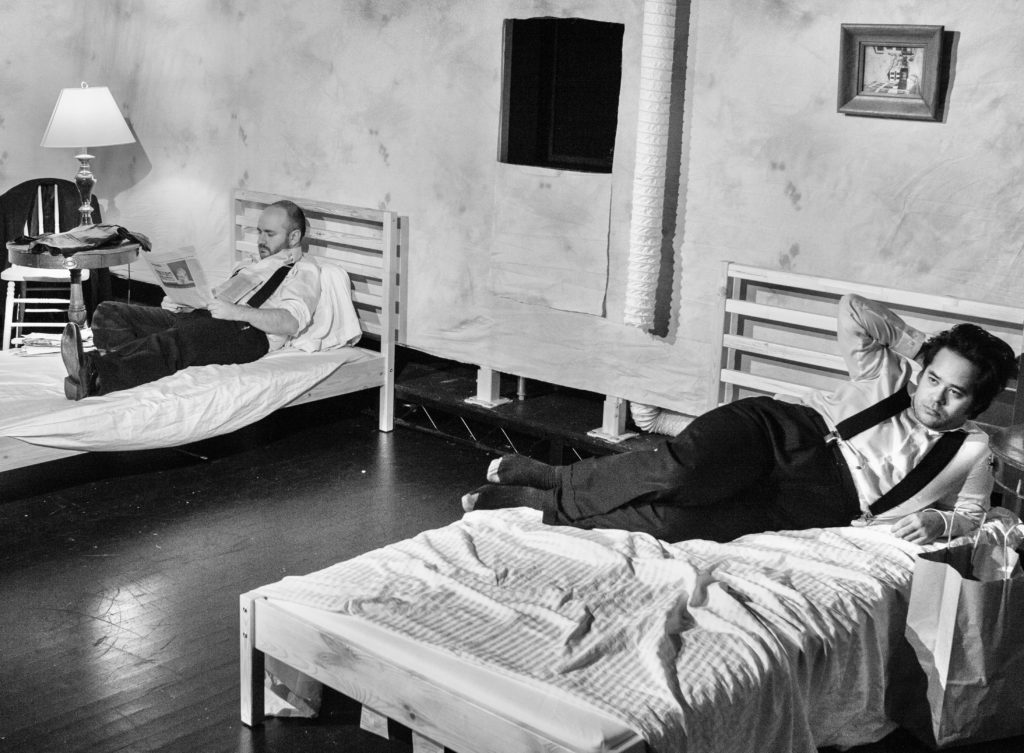

Critics often point to the use of an “enclosed space” in Pinter’s plays. Not only do we, as the audience, not know how the characters got to this space on the stage, we also slowly discover that the world outside the stage is either irrelevant or closed off to the characters themselves – sometimes quite literally, with locked doors. Within this space, the characters struggle to communicate with one another. In some ways, they communicate most effectively through pauses and long stretches of silence, that is, when they are not talking to one another. When they do speak, the dialogue is often awkward and strained, and they often seem not to listen to one another but rather talk past one another.

A character will make a statement, for example, “I could be your best friend,” which a few moments later he or she will deny having said. Is that forgetfulness? Or lying? In long scenes where characters exchange dialogue consisting of telegraphic phrases, suddenly one of them will launch into a logorrheic monologue, spewing out a torrent of speech that is at-once aggressive and unsettling but more tellingly – and counterintuitively – screens the real message the character wishes to convey. That is, many more words but much less real communication. Welcome to the world of Harold Pinter.

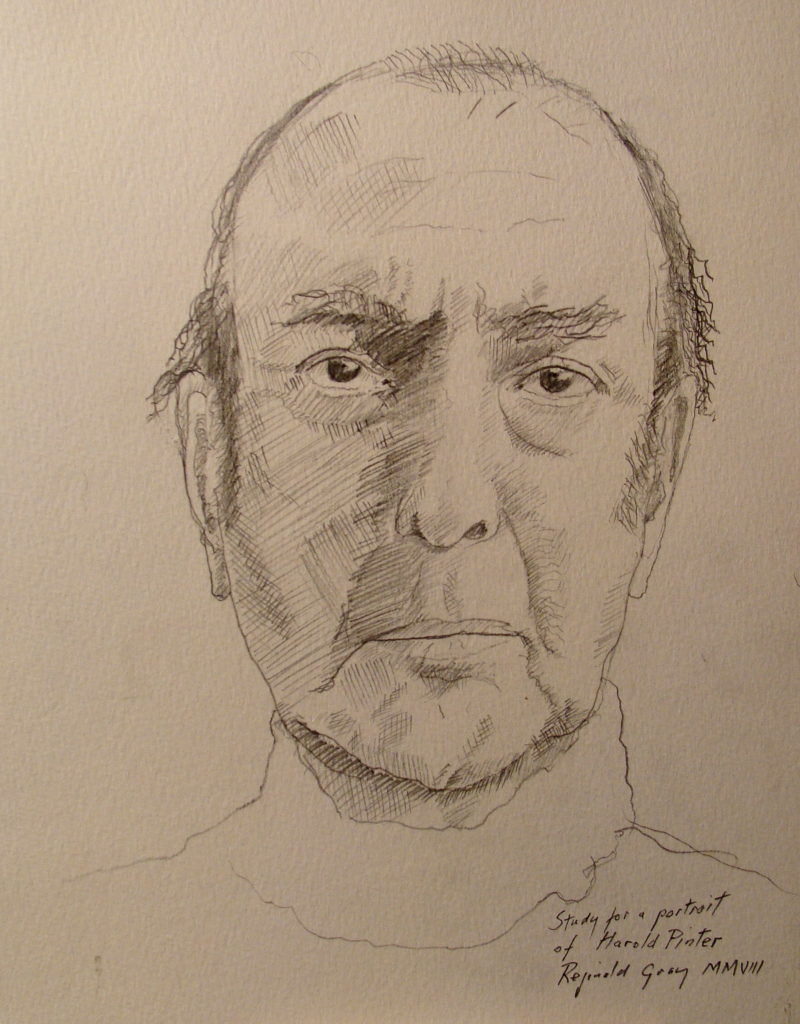

Harold Pinter insisted that he lived a happy life but did not write happy plays. He certainly lived a long life, passing away at age 78 in 2008, three years after winning the Nobel Prize for literature. But an outside observer might argue that though he considered his own life to be happy, he certainly did not make many of those around him happy. Examples are his first wife, Vivien Merchant, and their son, Daniel, who changed his surname, cut off contact with his father, and did not even attend his funeral.

Still a teenager, attending Hackney Downs School in London, Harold began acting in school productions. After graduation, his interest in drama took a stronger hold as he enrolled in the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art for a couple of terms but soon soured on the school, quit, and was promptly drafted into the British Army. To avoid the draft, he declared himself a conscientious objector, a request eventually granted. Pinter had made his first political statement.

In his first substantial gig, Pinter joined a repertory company that toured Ireland in 1951 and 1952. Throughout the mid-1950s, he pursued acting in London in a variety of roles, supplementing his income from the stage with odd jobs and waiting on tables. In 1956, he married Merchant (who later gained fame in her supporting role in the film Alfie, for which she was nominated for an Academy Award). From the get-go, their union churned in turmoil.

A year into his marriage, Pinter penned his first plays, The Room and The Birthday Party, both of which were box office flops. So disastrous was their reception, in fact, that only a review by a theater critic at The Sunday Times who praised Pinter’s “disturbing and arresting talent” managed to rescue his budding career as a playwright.

Over the next decade, Pinter wrote several plays that entered into the canon of “pinteresque” dramas, including The Dumb Waiter, where two hired killers, enclosed in a basement room, await an order to carry out their next hit but instead receive perplexing messages delivered to them from the room above, a former restaurant, via a dumb waiter. Or The Caretaker, in which three characters, two brothers and a tramp they have rescued from the streets, successively deceive and mock one another after the two have separately offered to hire the duplicitous tramp to watch over their cluttered apartment. These were followed by a dozen of what still are among Pinter’s most popular plays, including The Hothouse, The Homecoming, Old Times, and – the oddest of all – No Man’s Land.

In the late 1970s is where we reach one of Pinter’s most acclaimed masterpieces, Betrayal. Uncharacteristically, this play finds its origin in Pinter’s personal life. In 1975, he started an affair with Lady Antonia Fraser and, two years later, filed for divorce from Vivien Merchant. In the midst of this turbulence in his private life, Pinter set to work on Betrayal. As the play opens, two former lovers, Jerry and Emma, meet in a pub in 1977 to reminisce about their long, quieted affair, which they are convinced had remained unknown to their friends and family. Through the six subsequent scenes, the action moves backward in time, during which we learn that Jerry’s wife and Emma’s husband not only knew about Jerry and Emma’s liaison but had separately carried on their own secret love affairs. Everyone in this play appears to deceive everyone else; layers upon layers of betrayal emerge. In the final scene, Jerry professes his desire for Emma, the act that had launched their affair. (Seinfeld fans might recall an episode entitled “Betrayal” where, attending a wedding in India, Elaine lets slip that she had had, let’s say, intimate relations with the bridegroom, while Jerry admits an earlier dalliance with George’s girlfriend. A character named Pinter pops up in the episode and, like Pinter’s version, the action moves backward in time.)

Pinter’s marriage to Lady Fraser apparently brought him the domestic bliss missing earlier in his life as he embraced his many stepchildren and step-grandchildren. His former wife, Vivien Merchant, on the other hand, sunk into depression and alcoholism, which ended her life in 1982 at age 53.

In contrast to the prickliness we find in Harold Pinter’s politics and plays, his namesake street in Laureate Park offers tranquil, leafy scenes that might vaguely call to mind a quiet English village perhaps, say, in the Cotswolds, a short drive west from London. You might even say that strolling down Pinter Street on a sunny morning would be the perfect antidote to watching a Pinter play. You will at least know in advance how your stroll will finish, at the lovely Crescent Park at one end, or at the equally attractive Square Lake at the other. With those pleasant thoughts in mind, let’s leave the ambiguity and awkwardness of the next Harold Pinter play to one of those occasional days when our Central Florida skies grow overcast and grey. Seldom does the weather of sun-soaked, fun-loving Orlando turn, shall we say, pinteresque, but when it does…

An enjoyable read Dennis. I well remember growing up watching some of Harold Pinter’s movies , in particular Accident & The Go Between .

Wonderful article! I live on Pinter Street. The article contains a great mix of historical facts and pop culture and local trivia.