One way to win a Nobel Peace Prize is to make Alfred Nobel fall in love with you. Then convince him to fund provisions for such a prize in his will.

Just kidding … but not entirely. There is no real evidence that Alfred Nobel harbored truly romantic feelings for the lovely Austrian countess Bertha Kinsky, whom he first met when she spent a week in Paris in 1876 employed as his secretary and housekeeper. If their relationship was not, let’s say, steamy, the two did become intimate friends over the last quarter century of Nobel’s life. And what drew them so closely together – on an intellectual plane, of course – was their common passion for the cause of peace. You might say that Alfred and Bertha were soulmates, though Bertha was happily married for those many years.

This chance encounter of the highly-educated yet enticing Austrian countess and one of Europe’s most accomplished bachelors makes for a magical story in itself. But even without crossing paths with Alfred Nobel, Bertha already lived a life resembling that of a fairytale. Though born Countess Kinsky in Prague in 1843, Bertha’s blood was insufficiently pure by the demanding standards of Austrian nobility of the era. (Let’s just pause right here to say that the notion of nobility is an absurd concept in our century, but to understand Bertha von Suttner, we must reckon with the environment in which she was raised.) Her widowed mother’s diluted genes Bertha could overcome, and in fact by her 20s, she had been proposed to twice. The first of these was to be an arranged marriage to an elderly gentleman, whom Bertha rejected upon meeting him; her second prospective fiancé died suddenly on a sea passage to New York escaping his creditors.

What Bertha could not surmount, though, was the grave depletion of family income resulting from her mother’s gambling losses at spas such as Wiesbaden. Bertha had benefited from a tutored education and was highly proficient in English, French and Italian, in addition to her native German. So, at age 30, with no marriage prospects in sight and having failed in pursuing a career as an opera singer, she secured a position as governess for four children of a wealthy family in Vienna, where she promptly fell in love with the eldest son, Arthur von Suttner, seven years her junior.

Arthur’s mother, though, had no intention to allow her son to marry the insufficiently noble Bertha and conceived a plan to separate the two lovers as far apart as possible. By mail, she helped to procure the secretarial position for Bertha at Alfred Nobel’s office in Paris. Undeterred by his parents’ disapproval of his wedding hopes, Arthur telegrammed Bertha to plead that he could not “live without her.” Jotting a quick resignation note to Alfred, who was on travel for business, Bertha returned to Vienna to elope with her beloved Arthur, marrying in an obscure church outside the city. Unmoved, Arthur’s parents cut off his baronial income, leaving him no choice but to seek a living outside of Austria.

Years earlier, at Bad Homburg, Bertha had met a Georgian princess, Ekateriné Dadiani, to whom she now wrote in desperation, seeking refuge and possible employment in her principality of Mingrelia. Ekateriné cabled back, “Welcome.” Clutching their dwindling funds, Arthur and Bertha sailed across the Black Sea to Georgia’s western shore. From there, they traveled for days by carriage and on horseback, accompanied by Prince Niko himself, the titular head of the land, toward Ekateriné’s cliffside castle. Along the way, lavish dinners and entertainment celebrated the honored guests.

Reunited finally with Ekateriné, they were however stunned to learn that the Russian Empire, which in 1801 had added Mingrelia to its domains, had now taken away all political authority from both her and her son, Prince Niko. No palace employment would be forthcoming for Arthur and Bertha. To survive in this exotic, remote land, the newlyweds would have to cobble together meager incomes through tutoring and odd jobs. Eventually, they settled down near a secluded village and took up writing articles for German and Austrian periodicals. The couple endured a life of poverty in Georgia for nine years, until 1885, when Arthur’s family relented and invited him home to Vienna.

Relieved from their exile, the von Suttners wasted no time to travel to Paris, where Alfred Nobel introduced them to leading literary salons, through which they befriended France’s intellectual giants of the day, including Emile Zola and Alphonse Daudet. The learned discussions at these gatherings further instilled in Bertha her passion for literature. While in Georgia, Bertha had published her first two books, in addition to penning countless articles, the start of a literary output that eventually grew to include dozens of novels. Most of these are now forgotten, except one, Lay Down Your Arms (Die Waffen Nieder!).

In Georgia, during the 1877-78 Russo-Ottoman War, Bertha’s cottage had abutted the front lines, and she experienced firsthand the horror of war in its rawest form. The trauma sparked in her a serious interest in pacifism. In 1889, back home in Austria, Bertha poured out her hatred of war in Lay Down Your Arms, which swiftly became a bestseller throughout Europe. Praise even came in the mail from Leo Tolstoy, who equated the novel with Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. What Stowe had accomplished in ending slavery, wrote Tolstoy, Bertha would achieve in promoting peace. To the modern reader, Lay Down Your Arms plods along plotlessly, but the descriptions of the dead and dying on the battlefield of Königgrätz during the 1866 Prussian-Austrian War are expertly crafted. European readers had never before confronted such haunting accounts of the effects of war.

The success of Lay Down Your Arms made Bertha an instant celebrity, and she soon dove into a dizzying range of roles that included promoter of peace organizations, editor of her Die Waffen Nieder! pacifist magazine, and much sought-after speaker. In 1892, Bertha convinced Alfred Nobel to travel to Bern, Switzerland, to observe the proceedings of the International Peace Congress, after which he invited her to dinner in Zurich. At that dinner, Albert raised, for the first time, the idea of including provisions for a peace prize in his will. He soon passed away, and the first Nobel Prizes were awarded in 1901. Four years later, Bertha won the Peace Prize, the second woman, after Madame Curie, to be awarded a Nobel Prize.

Until 75 years ago, Europeans regularly settled their differences through horrifically destructive wars that grounded up the lives of millions upon millions of victims. These days, in Western Europe at least, toughly-fought contests on soccer pitches have supplanted these once-ceaseless armed conflicts. Though Bertha von Suttner’s decades-long campaigns to lay down arms did not prevent two World Wars, her tireless campaigns to promote pacifism arguably laid the foundations of organizations designed to secure European – and global – peace following World War II. In our neighborhood, we honor Bertha von Suttner with an afterthought of a street where, until recently, only local longhorn cattle grazed. A year or so ago, a special building rose on Suttner Avenue, a lone structure bordered by those cattle paddocks. And what is that structure? An indoor soccer field and training facility.

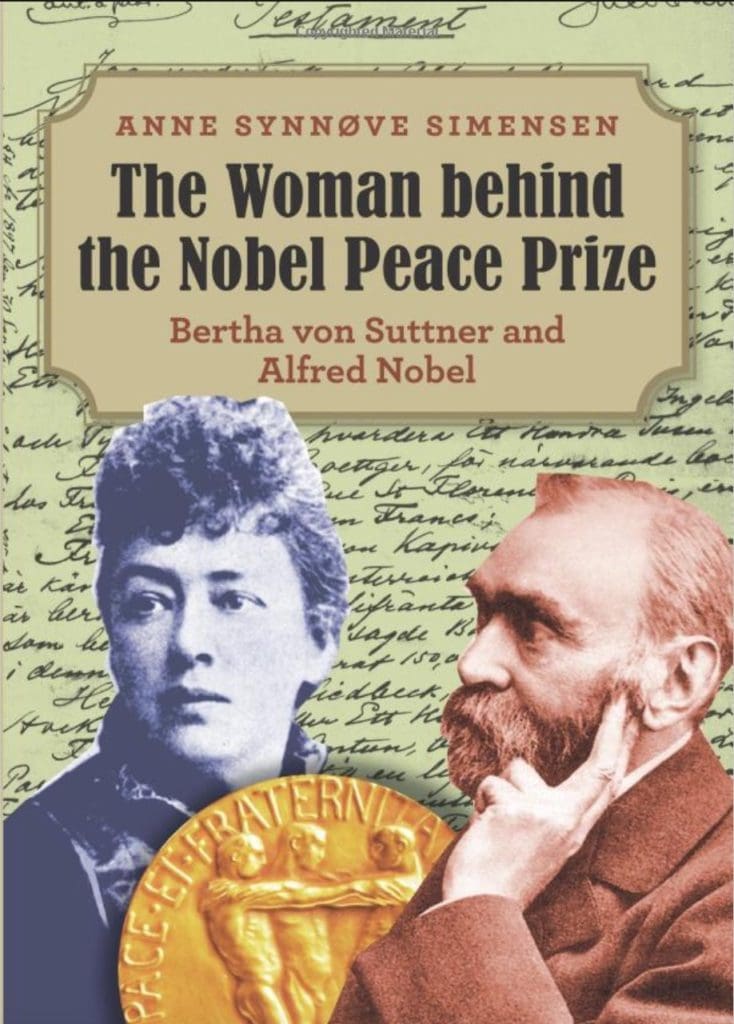

True, Lay Down Your Arms is not a fun or easy read. If you wish to learn more about the life and remarkable achievements of Bertha von Suttner and her relationship with Alfred Nobel, you might dip into a fascinating biography entitled The Woman behind the Nobel Peace Prize by Norwegian author Anne Synnøve Simensen. Or read one of her lectures, such as her address to the October 1904 International Peace Conference in Boston.