We Lake Nona residents often proudly point out to visitors Nemours Children’s Hospital on Nemours Parkway. We so admire that stunning teal and butterscotch structure, but isn’t that an odd name, Nemours? Where did that name come from? To answer that question, we have to peek back – believe it or not – to the French Revolution.

In the spring of 1794, a singularly accomplished nobleman named Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours sat in a prison in Paris, somberly awaiting his turn to be carted away to the guillotine. A true product of the Enlightenment, Pierre had initially studied medicine but shifted his intellectual energies to economics, diplomacy and statecraft, rising to serve as advisor to Louis XVI, who ennobled him, appending “Nemours,” his home province, to his last name. An abbreviated account of Pierre’s achievements would fill books. While his writings on economics influenced Adam Smith, Pierre helped to negotiate the 1783 Treaty of Paris ending our War of Independence, befriended Thomas Jefferson, and served on the committee that dispatched Napoleon to Elba.

More importantly, Pierre was blessed with luck. Days before his expected execution, the revolutionary leader who had him arrested, Maximilien Robespierre, suddenly met his own political downfall, and Pierre was saved. He and his two sons lingered in Paris for a few years but in 1800 emigrated to Delaware. There, the younger son, Éleuthère, founded a gunpowder business that would become the DuPont company. By then, Pierre, reflecting on his earlier medical studies and the hardships of the French Revolution, had instilled in his sons a commitment to alleviate human suffering.

Fast forward 221 years. This summer, an Images of America photo history penned by the current president and CEO of Nemours Children’s Health, R. Lawrence Moss, MD, FACS, FAAP, lands on our desk. In this volume, Dr. Moss and his collaborators trace the story of the DuPont family and the origins and growth of the foundation that fashioned Nemours Children’s Health while dropping hints about future directions for that organization. Pierre’s life and adventures occupy merely the first page of Dr. Moss’ book; his son’s founding of the DuPont company merits another page. But we soon come to the 1860s, when the real star of the Nemours story enters the scene. This is Alfred I. duPont, Éleuthère’s great-grandson, the man who founded the organization and whose spirit, to this day, is embodied by Nemours Children’s Health.

Alfred was a cut apart from the other members of the privileged DuPont clan. As a child, he preferred the company of the family firm’s mill workers, and following two years of study at MIT, he joined the family’s gunpowder business as a common laborer. Through hard work and consummate mechanical skill, Alfred rose through the company ranks, earning in the process, with his 200 patents, a reputation as one of the nation’s foremost gunpowder experts – as well as considerable wealth. His first marriage, which produced four children, ended in divorce, but in 1907, he remarried to a second cousin, Alicia Bradford, and built for his new bride a 77-room home, the Nemours estate in Wilmington, Delaware. Sadly, the couple lost two infant children, and tragedy struck thrice with Alicia’s death in 1920. But during their happy marriage, Alicia had steered her husband toward a commitment to philanthropy and nurtured in him an enduring interest in bettering the lives of afflicted children. Grieving the loss of his wife, Alfred drafted a will that called for the construction of a “Nemours Memorial Home for Crippled Children” on the grounds of the Nemours estate.

In his third wife, Jessie Dew Ball, Alfred found a soul equally dedicated to caring for children’s health and a partner destined to play a key role in the Nemours story. For financial and personal reasons, Alfred moved his principal residence to Jacksonville. Having separated himself from the DuPont family businesses, he began investing in Florida banks and continued to amass great wealth.

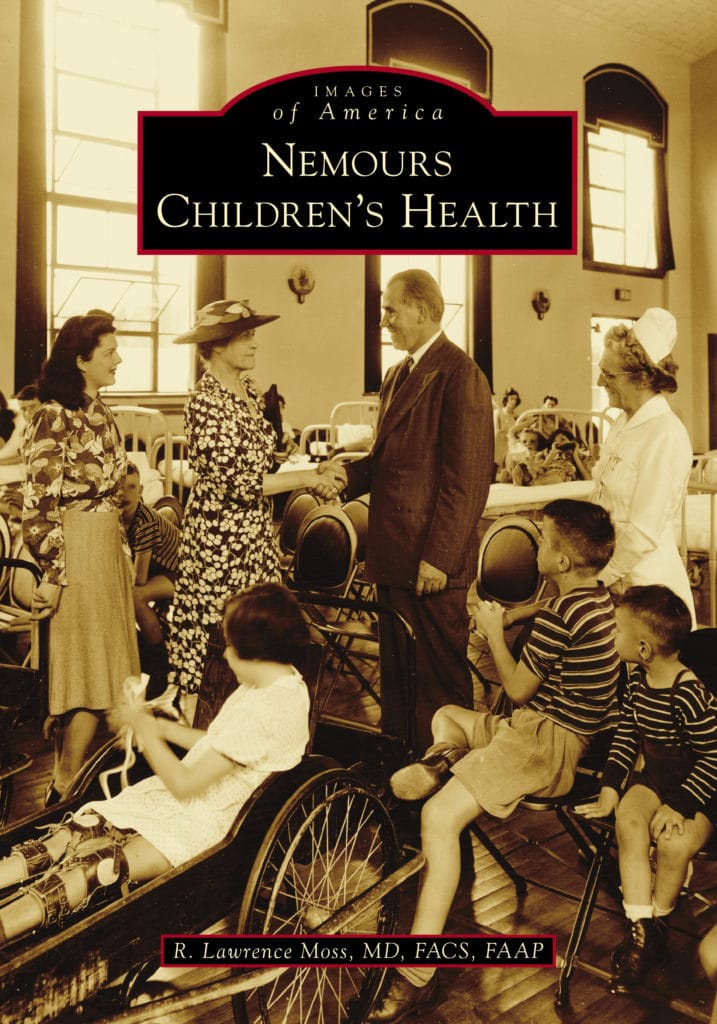

At the age of 70, Alfred passed away but left in his will an urgent task for his widow Jessie: to establish a foundation that would build a children’s hospital in Wilmington. Jessie set immediately to work, and in June 1941, the Alfred I. duPont Institute opened to receive its first young patients. The goals of the institute initially focused on “patient care, education, research, and post-graduate training,” with a special emphasis on orthopedics. For the first director of the institute, Jessie oversaw the selection of noted orthopedic surgeon Alfred Shands, which became a position he held for the next 32 years.

Dr. Shands not only laid a secure basis for the medical and research work of the organization but expanded both the healthcare and geographical scope of Nemours Children’s Health, which now operates in six states. Over the past several decades – to cite a few of its achievements – the foundation has built flagship hospitals in Delaware and Florida; launched Kidshealth.org (the most Googled website worldwide for children’s health); cemented a pediatric residency partnership with the prestigious Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia; and constructed numerous children’s clinics. From an aspiration tersely expressed in Alfred duPont’s 1935 will, Nemours has grown to become a world-class medical network to care for children, among the best of its kind anywhere. Having accomplished so much over the past eight decades, what direction does Nemours take now?

Dr. Larry Moss is a man on a mission. A mission to direct the resources and sweep of Nemours to redefine children’s health in this country and, in his words, to move “well beyond medicine.” Currently, he tells us that our nation’s healthcare system focuses on two main goals: volume and complexity of medical services. This system does an outstanding job in saving the lives of children who suffer from rare or difficult-to-treat illnesses. But this same system performs miserably in safeguarding the overall health of children in this country. The United States ranks well below the achievements of other developed countries in delivering satisfactory health to our nation’s children, for example, in such indicators as life expectancy, infant mortality, and management of asthma and diabetes. In this country, we tend to equate health with medical care, but about 85% of children’s overall health is determined by multiple societal factors, such as education, food security, and freedom from poverty. For Dr. Moss and his colleagues, it is imperative that we “change the meaning of health to something bigger, more expansive, and more needed and wanted by our families.” A monumental task if there ever was one.

Nemours Children’s Hospital stands in a corner of Laureate Park, tucked against the Lake Nona Boulevard interchange with Route 417. This architectural marvel reflects openness and flexibility, a result due in part to the active involvement of parents and children in the design of the structure. But there is one design detail that exemplifies both the hospital’s caring attention to its patients and its close engagement with the community. Each evening, the hospital’s windows radiate a kaleidoscope of delicately dappled lights, in blue, green, orange, yellow and violet. In Lake Nona, we love color on every structure we build, but the evening lights on Nemours Children’s Hospital are something special. Doctors tell us that children who enter hospitals fear most of all a loss of control. At Nemours, each child can choose at will the color of the lights that illuminate his or her room. Thus, the children admitted to Nemours not only gain a measure of control over their new surroundings but also send forth small beacons of hope to the community that add so much to the beauty of our neighborhood’s nightscape.

As this century’s third decade opens, Dr. Moss and the 8,500 dedicated associates at Nemours face ever-increasing challenges to secure the health and wellbeing of our children’s healthcare, challenges in which as a nation we all share. To find our way forward, it is often helpful to study the past to see where we have come from. We find that history of Nemours in Dr. Moss’s engaging new Images of America volume.