In honor of Breast Cancer Awareness Month, we’re highlighting the work our scientists are doing toward the next generation of breast cancer therapies.

In honor of Breast Cancer Awareness Month, we’re highlighting the work our scientists are doing toward the next generation of breast cancer therapies.

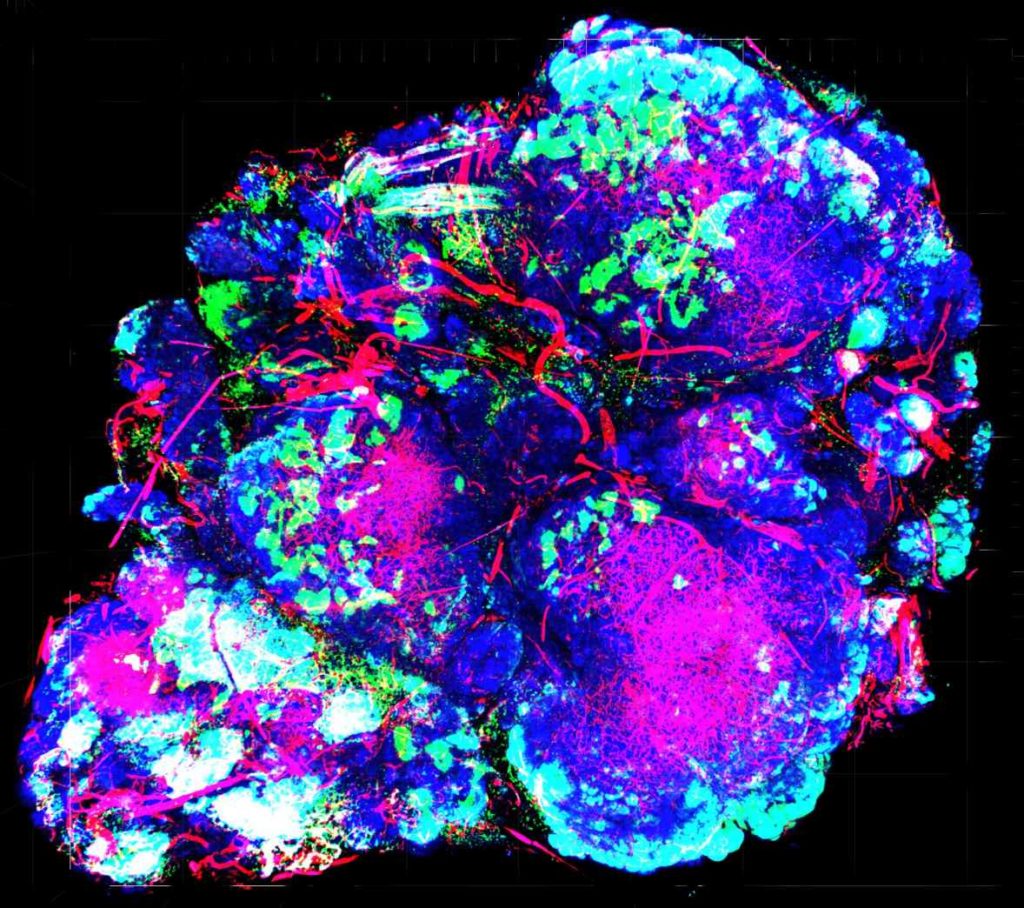

Providing more oxygen to a tumor might seem like exactly the wrong way to treat cancer. But Masanobu Komatsu, Ph.D., Associate Professor in the Cardiovascular Metabolism Program and the NCI-designated Cancer Center at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in Lake Nona, is trying to find treatments that do exactly that. Enhancing a tumor’s blood supply, which carries oxygen to cancer cells, actually lowers the chance that the cancer will spread.

“We’re aiming to minimize one of the most challenging and devastating aspects of breast cancer – metastasis,” Komatsu said. ”Mortality rates for metastatic breast cancers are still incredibly high. Of the patients with cancer that has spread and led to tumors in other organs, almost 80% will survive less than five years.”

Cancer cells become more likely to move into other tissues as they adapt to a low oxygen environment due to a tumor’s defective vasculature. Because these blood vessels grow abnormally fast and malformed, oxygen is limited in the tumor’s interior. However, the cancer cells buried within continue to grow and mutate, so some can survive the lack of oxygen. The master switch that enables cancer cells to generate energy by alternate means also triggers changes that let them enter the circulation and find new homes.

Strengthening the blood supply also could help to make the cancer more vulnerable to therapeutic attack, Komatsu added. “Improving the circulation inside a tumor would help anticancer drugs – and the body’s own T cells, which also help eliminate cancer – reach all the tumor cells, and increasing oxygen levels helps sensitize them to radiation and immunotherapy.”

Studies using mouse models of disease suggest that normalizing tumor blood vessels confers such benefits, but existing drugs known to stabilize the vasculature have shown limited benefit. Komatsu and his lab are looking for better therapies by screening microRNAs, small pieces of genetic material that regulate gene activity.

With funding from the Florida Breast Cancer Foundation, the scientific team is testing each of hundreds of microRNAs to look for those that affect signaling pathways controlling the stability of tumor blood vessels. The microRNAs that come up positive could either be developed as drugs (to be used in combination with other cancer-killing treatments) or be studied further to find new drug targets.

“This strategy is relevant not only to breast cancer but also to any solid tumor,” commented Komatsu. “The therapies we hope to find could help a huge number of patients.”