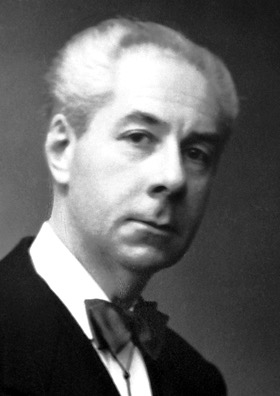

With this article, we continue our series of columns dedicated to celebrating the lives of the Nobel Prize winners honored by the names of the 125 streets in Laureate Park.

I wonder if any homeowner on Dugard Court has ever read anything written by the French author Roger Martin du Gard? Or for that matter, anyone in Lake Nona or Orlando or even all of Florida? Martin du Gard is not exactly a household name in this country, and though my friends in France seem quite familiar with him, he merits only a brief mention in an official guide to 20th century French literature that has stood on my bookshelf over the past three decades.

Laureate Park, too, has taken a desultory approach in honoring this otherwise esteemed French novelist. In our neighborhood, Martin du Gard’s three-part surname has been indelicately truncated to its two final units then fused together to form “Dugard.” Few of us have last names composed of three words, but this awkward abbreviation of what normally should be called Martin du Gard Court might be likened to a hypothetical “Quincyadams Way” or “Lutherking Boulevard.” To add to the awkwardness, Martin du Gard’s own father, born Paul Martin, attached “du Gard” to his last name to distinguish his brood from the apparently unwelcome extended Martin relatives. You might contend, though, that such idiosyncrasies in our local street names sprinkle a dash of charm upon our community. And what is so important about a last name anyway?

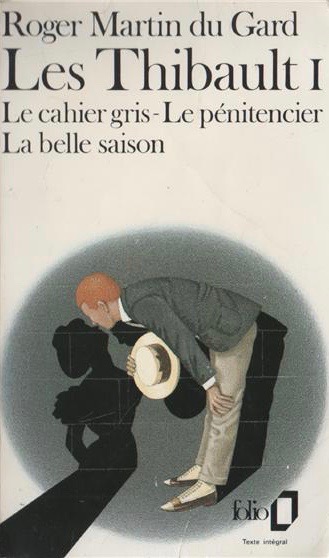

Any columnist profiling the lifework of Roger Martin du Gard risks producing text that devolves swiftly into a book report. This is because Martin du Gard today is known essentially for just one book, a novel called Les Thibault (The Thibaults). Martin du Gard was a big fan of Leo Tolstoy, the author arguably blessed with the greatest narrative skill of all time. Perhaps, though, he mainly admired Tolstoy’s skill at writing really long books, since Les Thibault is not just one book but a collection of several novellas strung together into what the French call a roman fleuve (river novel). And in this case, a really long river novel – clocking in at 2,500 pages, about twice the length of Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Martin du Gard’s prodigious effort nevertheless pleased the Swedish Academy’s literary judges, since they awarded him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1937 mainly for this one novel.

The plot of Les Thibault smolders in the Paris of the 1910s. Two brothers, Jacques and Antoine Thibault, chafe under the despotic tyranny of their ultra-Catholic father. In the opening pages, 15-year-old Jacques has recently befriended a Protestant schoolmate, Daniel de Fontanin, and has shared with him intimate confessions in a grey notebook discovered by his father. Desperate to escape his suffocating home life, Jacques absconds with Daniel by train to Marseille, where the penniless pair last not a couple of days before being detained by local police. Mr. Thibault dispatches Antoine, the future medical doctor, to Marseille to recover the runaways. Upon arriving home, Jacques is consigned to a reformatory north of Paris conveniently managed by his father’s foundation where, after a year in near isolation, Jacques emerges an earnest, if cowed, penitent. His contrition is short-lived, however, as he renews a now uncomfortable friendship with Daniel, contact with whom Mr. Thibault has categorically prohibited, and succumbs to a hopelessly unrequited obsession with Daniel’s sister, Jenny. Through the next 900 pages, the plot rambles slowly through scenes of the two brothers’ daily struggles with their father, in episodes that only occasionally offer narration worthy of comparison to Tolstoy. In one passage, Martin du Gard competently conveys Antoine’s surgical abilities in an operating room hastily assembled in a sweltering Paris row house, where he toils to save the fragile life of a child nearly crushed by an overturned cargo van. Elsewhere, pages upon pages describe in copious detail, in scenes difficult to watch, Mr. Thibault’s struggle with what appears to be cancer of the kidneys, though diagnoses in the early 20th century were only approximate.

Martin du Gard may have struggled to weave engaging plots or sketch likeable characters, but he was unquestionably a master of prose. Consider this one sentence describing the charm of a Swiss city along Lake Geneva: “All of Lausanne’s aged rooftops tumbled down towards the lake in an inextricable tangle of grayish packsaddles whose outlines were melted by mist; these tiles, riddled with lichens, seemed steeped in liquid like felt.” Expand such prose to fill nearly three thousand pages, and you will have an idea of a brilliant wordsmith at work. Let’s just say that Les Thibault is a sprawling epic that documents the conflicts and contradictions tugging at the frail fibers of French society as Europe bumbles into World War I.

Sadly, this book report will remain unfinished because I cannot tell you how Les Thibault ends. As I closed the second of five volumes of Les Thibault, I finally admitted to myself that Roger Martin du Gard had defeated me, and that chances were low that I would ever look into his other major works, most notably his biography of writer friend (and fellow Nobel laureate) André Gide.

Not often do Americans summon sufficient courage to admit that the French excel in many areas – such as fashion, cuisine, and yes, the number of all-time Nobel laureates – where our achievements appear to be of a lesser order. In my travels in France, I have been charmed to observe how the French have refined details of daily life still seemingly absent in this country. To cite one example, the French do not merely honor their authors and artists with place names, but do so with flair: A quick Google search produces several instances of an Avenue Roger Martin du Gard throughout the Hexagon, a common nickname for France. In Lake Nona, we have made the first steps in honoring the most accomplished individuals on our planet. But isn’t there always room for improvement?

Next month: William Beebe, Bathysphere Biologist