This is the 16th in a series of articles that celebrate the lives of the Nobel Prize laureates whose names grace the 130+ streets of Laureate Park. These laureates are extraordinary individuals, who through their lifetime achievements have made our daily lives immeasurably richer, often in ways not readily evident. Two accomplished Tagore enthusiasts in India contributed to this article: Gautam Gupta, author of 1857, The Uprising, and editor and publisher Suvadip Bhattacharjee.

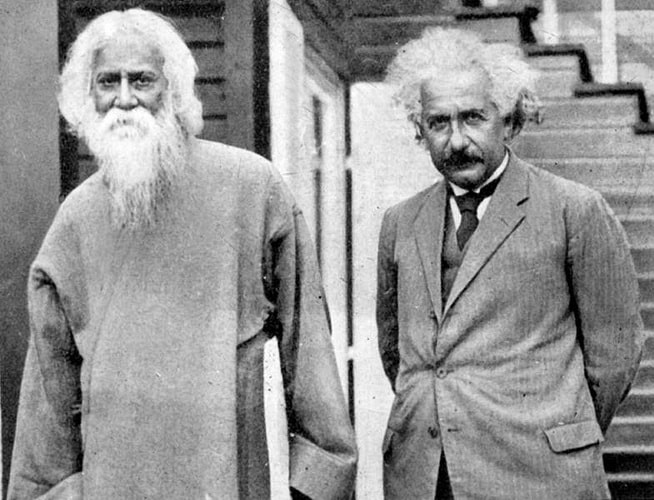

In the summer of 1930, Albert Einstein invited Rabindranath Tagore to his home near Berlin to engage him in a profound philosophical discussion about the nature of reality, truth, and beauty, a conversation historians rank among the weightiest of the 20th century. Photos of the encounter show Tagore’s scraggly and shockingly white goatee tickling his upper chest while the mop atop Einstein’s capacious cranium spiraled recklessly in all directions. The purpose of this colloquy between two intellectual giants – conducted through interpreters since Einstein was not yet fluent in English – was to bring a measure of clarity to mankind’s understanding of the complementary roles of spirituality and science. For Tagore, reality, including all matter in the universe, could be considered to exist to the extent that it is perceived by the human mind. Arguing the more commonly-held view, Einstein maintained that our world is a reality “independent of the human factor.” In a nod to comity, Einstein did accept Tagore’s argument that beauty can only exist through its discernment by the five human senses. That is, without humans, there can be no beauty.

Though the lifework of Albert Einstein radically transformed our understanding of the cosmos, his achievements remained largely confined to the discipline of physics. In contrast, Rabindranath Tagore is regarded as one of the few true polymaths of all time, along with the likes of Aristotle, Leonardo da Vinci, and Benjamin Franklin. A polymath, we are told, is an individual “well informed and learned about a wide variety of topics.” Tagore did not just learn widely, he produced widely. The vocations at which he excelled were those of poet, philosopher, novelist, composer, essayist, choreographer, lyricist, painter, playwright, humorist, educator, film director, lecturer, and actor.

Born into a large, wealthy, intellectual family, Tagore got an early start in his literary career, publishing his first lines of poetry at age 14 and his first operetta six years later. Thus kickstarted a prodigious artistic output that spanned the next 60 years as Tagore composed upwards of 40 plays, nine novels, stacks of poetry, and over 2,000 songs, including the national anthems of three countries. On his deathbed in 1941, Tagore was still churning out poems. Nearly eight decades later, Tagore’s artistic creations – his songs and dance dramas – seem as lively and popular as ever. On Spotify, you will find – believe it or not – a Rabindranath Tagore radio station, and currently streaming on Netflix is Red Oleanders Raktokorobi, a 2018 film that traces the trials of an Indian theater troupe staging Tagore’s play of that name.

The polymath of India seems hidden in plain sight, at least to Western eyes. With little effort, you will uncover on YouTube a 1938 film version of Tagore’s novel Gora, which explores the complex social dynamics in Indian families whose members adhere to conflicting religions: Hinduism, Islam, and Brahmo Samaj, a faith cofounded by Tagore’s own father. Also on YouTube is a brilliant 1961 biography of Tagore by the noted Indian film director Satyajit Ray. In one arresting scene, Ray portrays a deeply mystical experience that overcomes a twenty-something Tagore one dawn as he ventures out of his home on Kolkata’s humble Sudder Street to observe the sun shimmering through the branches of a neighboring tree. Tagore was transfixed. Describing the experience years later, he wrote that, at that moment, a covering suddenly fell from his eyes, and he saw the world “bathed in a wonderful radiance, with waves of beauty and joy swelling on every side.” Seeking to enhance this state of bliss, Tagore traveled shortly thereafter to the Himalayas. But those mountains denied him this new transcendent vision that only the prosaic Sudder Street could reproduce.

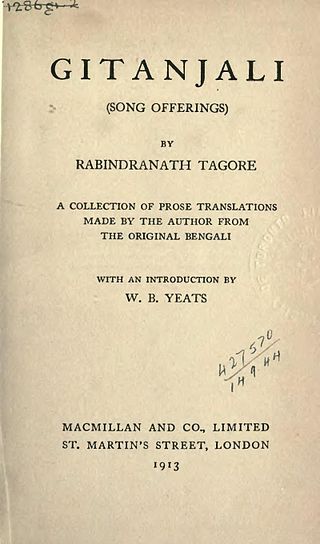

Throughout his life, Tagore traveled the world widely. A 1912 trip brought him to England, where the Irish poet William Butler Yeats became enthralled by a collection of poems called Gitanjali that Tagore himself had translated from the original Bengali into English. Yeats offered to pen an introduction to the collection, which quickly became a European bestseller. The Swedish Academy, too, noticed Tagore’s verse and, the following year, made him the first non-European to win a Nobel Prize in literature. Like Lu Xun of China or the Russian Alexander Pushkin, Tagore had single-handedly modernized the literature of his home country. To Western eyes, the poems in Gitanjali (“Song Offering” in Bengali) seem much like secular hymns in free verse, but one might wonder to what extent the English translations of Tagore’s literary output retain the lyrical beauty of the original Bengali. (One might ask as well if Yeats was attracted to Tagore because he, too, struggled to revive the language of his native country, in his case Irish.)

Lake Nona’s stress on community wellness draws many new homebuyers to the area. We live in a town where neighbors convene to cycle, practice yoga, play pickleball, or just hike around the Nonahood’s various unnamed lakes with a dog or two in tow. Some of us occasionally manage to rise at 6:30 a.m. for an early morning meditation session at Dockside led by local yogi extraordinaire Natalia Foote. Were you to seek a peaceful spot nearby to work on your meditation skills on your own, you could easily choose a number of appealing outdoor venues, such as Crescent Park or the greenery surrounding Square Lake. One spot you would be unlikely to practice meditation, though, is the parking lot in front of the neighborhood Walmart. But there, you will find Tagore Place, the street honoring the man so influential in bringing to the West the achievements of India in philosophy and culture (among which yoga and meditation have arguably most impacted our daily lives).

Few of us would regard a parking lot as anything but commonplace. Yet Tagore found a special beauty in common places and likely would have been pleased to know that a street honoring his lifework should appear so outwardly ordinary. In these prosaic surroundings, Rabindranath Tagore reminds us that beauty really does surround us in our daily lives – if we only learn how to look for it.

Next Month: Louis de Broglie, Quantum Mechanic

Photos Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons