This is the 24th in a series of articles that celebrate the lives of the Nobel Prize laureates whose names grace the 130+ streets of Laureate Park. These laureates are extraordinary individuals who through their lifetime achievements have made our daily lives immeasurably richer, often in ways not readily apparent. The author wishes to thank Dr. Otto Phanstiel, professor of medical education at the University of Central Florida’s College of Medicine, who contributed to this article.

If you have ever seen the Broadway play Wicked or read the book of that name by Gregory Maguire, you may have marveled at the variety of creatures that populate the dominion of Oz. Such an abundance of beasts, you would think, should necessarily require the services of a competent veterinarian. No veterinarian, though, shows his or her face (or snout) in either book or play, and neither does an animal doctor of any description make an appearance in The Wizard of Oz, the 1939 film retelling the original novel by L. Frank Baum. Wouldn’t you think that Elphaba, aka the Wicked Witch of the West, could have benefited from the services of a professional caregiver to watch over the hundreds of winged monkeys in her aerial army?

The Land of Oz, of course, is a special country, the fauna found there like nowhere else. But Oz is a fictional country that burst forth from Frank Baum’s overactive imagination. Another quite real country on our own planet also harbors scores of unique animals found nowhere else. To name a few, there’s the kangaroo, koala, platypus, dingo, wombat and wallaby. That country, often nicknamed Oz, is of course Australia, a paradise for practitioners of veterinary science and home of octogenarian Peter Doherty, the first and only person degreed in that field to have won a Nobel Prize.

Growing up in Brisbane, the melanoma capital of the world, young Peter took pains to protect his fair skin, spending much of his time indoors with his head in a book. His extensive reading of the classics would later serve him well as clear and coherent writing is of special importance in assembling scientific papers. In his youth, one of Peter’s role models was his older cousin, Ralph Doherty, who had started a promising career in medical research. Chance brought the teenage Peter on a visit to the University of Queensland’s School of Veterinary Science, where, perhaps influenced by his cousin, that field of study grabbed his attention. By 1966, Doherty had earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees from that institution. To pay back his tuition, he took on a requisite five-year stint as a state veterinary officer, initially servicing livestock in rural Queensland, the Australian state that is bigger – believe it or not – than Alaska. Peter Doherty was about to leap into a career as a veterinarian. Suddenly, though, his scientific interests shifted as he was unexpectedly transferred to the state’s veterinary laboratory to carry out experiments in diagnostic pathology.

In that lab, Doherty discovered his real passion: immunology. But what path to take next? Having repaid his Queensland university loans, Doherty decided to seek a doctorate in that discipline at the University of Edinburgh. In that northern clime, the frequent cloud cover offered welcome relief for his sensitive skin and ample opportunity to enjoy the outdoors. Returning four years later to his home country, Doherty, now supplied with a Ph.D., dove into a researcher job at the John Curtin School of Medical Research in Canberra, where he teamed up with the Swiss biologist Rolf Zinkernagel to study viruses in different strains of mice, specifically the mechanics by which their immune systems react to viruses.

Let’s attempt to unpack the innovative work accomplished by Doherty and Zinkernagel in their Canberra lab in 1973.

We all know that viruses infect cells and reproduce inside them. The role of the immune system’s killer T-cells is to destroy the viruses, but to do so, the T-cells must first identify them. In their initial experiments, the two researchers observed that T-cells taken from another strain of mice failed to destroy the targeted viruses. This result surprised them. Further experiments revealed that the T-cells of a given strain of mice could destroy a targeted virus if they recognized both the virus antigen and a molecule of the major histocompatibility complex residing on the surface of the infected cell. The major histocompatibility complex, or MHC, is a set of proteins that allows the immune system to identify other proteins as either compatible (“self”) or foreign.

Doherty and Zinkernagel posited that in order to identify a cell as “self” or “non-self,” the receptors on T-cells must recognize the corresponding signals expressed by MHC molecules on the surface of the infected cell. “Non-self” cells – those necessarily containing viruses – would be slated for destruction. The duo’s findings published the following year in the scientific journal Nature provoked serious interest among immunologists worldwide. And by expanding our knowledge of the workings of the immune system in mammals, Doherty and Zinkernagel gave us a fuller understanding of the causes for tissue rejection in human organ transplants. In the words of Dr. Anthony Fauci, this was “an extraordinary discovery, one that ranks among the most important in the field of immunology because of its influence on subsequent research in infectious diseases, autoimmunity, transplantation immunology, rheumatology and cancer research.”

Following this major breakthrough, Doherty and Zinkernagel went their separate ways, each pursuing separate avenues of immunological research. In 1975, Doherty accepted a professorship at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia, where he focused on the causes of influenza, rabies and multiple sclerosis. Seven years later, he returned to the John Curtin School in Canberra before moving on in 1988 to a position as chairman of the Department of Immunology at St. Jude’s Children Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. There, in 1996, Doherty got the phone call from Stockholm announcing that he and his colleague of two decades past, Zinkernagel, had won that year’s Nobel Prize for medicine.

Normally, it is easy to keep up with a man who has already celebrated his 80th birthday, but not if that man is Peter Doherty. After winning the Nobel Prize, Doherty for many years divided his time between his job as professor at the University of Melbourne and his work at St. Jude’s, shuttling back and forth between Australia and America. In the early 2000s, Doherty launched a serious, long-term campaign to make use of his status as Nobel laureate to educate the world about immunology and, more generally, to advocate for science.

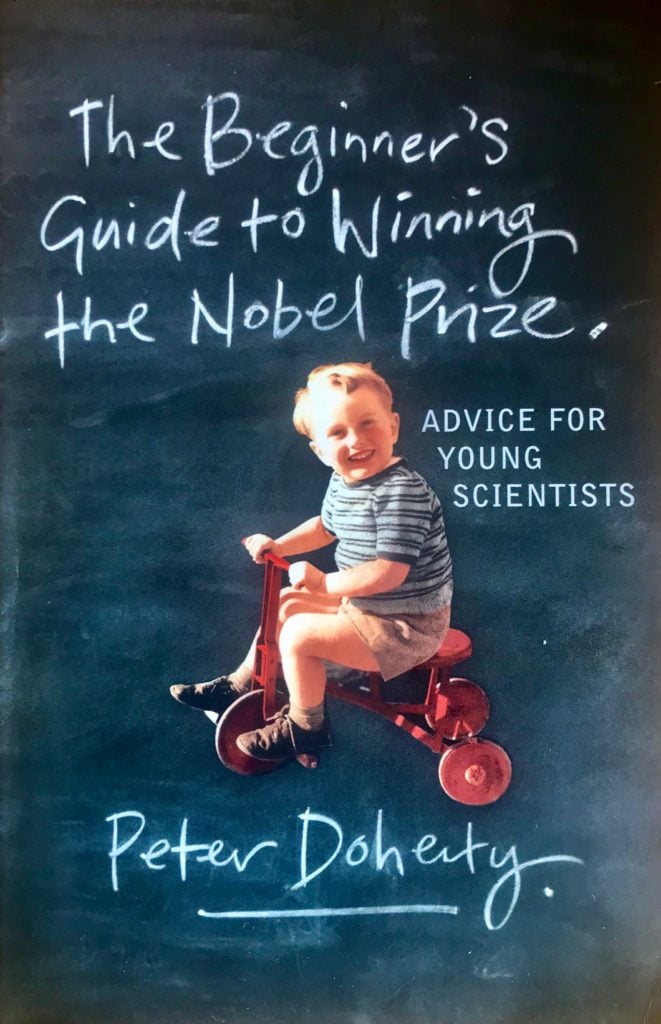

In 2006, he published his first semi-autobiographical book, The Beginner’s Guide to Winning the Nobel Prize, which offers useful tips for budding scientists, and he has followed up since with further books on such diverse subjects as climate change, the risks of pandemics, and how birds can foretell threats to human health. Even now, Doherty regularly issues dozens of tweets and, as founder of University of Melbourne’s eponymous Doherty Institute, writes a weekly column on topics of global scientific and political interest. This month, his latest book, An Insider’s Plague Year, is scheduled for release. The man’s intellectual energy seems limitless, almost supernatural. Something magical has suffused Peter Doherty’s long and productive life in science, and he has our profound gratitude for sharing much of that Ozian magic with us.