With this article, we continue our series of columns dedicated to celebrating the lives of the Nobel Prize winners whose names grace the 125 streets of Laureate Park. Dr. Otto Phanstiel, professor of medical education at the University of Central Florida’s College of Medicine, contributed to this article.

Women are not supposed to win Nobel Prizes for science. Or at least that’s what you would be led to think judging from the scarcity of these awards conferred upon women since the turn of the 20th century. To cite one statistic, of the 216 Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine awarded since 1901, women have won 12. Amid this want of recognition, one cannot help but regard the achievements of the exceptionally intelligent, inventive, and hardworking Gertrude Belle Elion as something rare and special.

Elion’s parents, emigrants from Lithuania and Poland, settled in New York City, where Robert Elion plied a trade in dentistry, a profession he vainly hoped his daughter would follow. Elion spent much of her happy childhood in the 1920s in the company of her grandfather in the Bronx, a borough then considered a suburb. But tragedy struck as Elion, at age 15, watched her beloved granddad succumb to stomach cancer. The trauma of this loss at such a sensitive age propelled Elion into a new lifelong commitment: to seek a cure for cancer. Enrolling at Hunter College in midtown Manhattan the following year (she had skipped a couple of grades in New York City public schools), she chose chemistry over biology for her major – admitting later that she found dissecting animals unappealing – and graduated four years later summa cum laude.

While her fellow chemistry majors at Hunter College, all women, sought teaching jobs, Elion, true to her goals, had set her sights on a career in scientific research. A newly minted alumna in the sciences entering the job market in 1937, though, did not readily find work of any kind. During the Great Depression, it was said you couldn’t buy a job, and women seeking professional work in those days faced even greater challenges. Yet somehow Elion managed to land a string of temporary lab positions, one of which paid the lordly salary of $20 a week, an income that enabled her to save sufficient funds to complete a master’s degree in chemistry from New York University. With a new diploma in hand, Elion landed on the street again, now more highly educated but still unemployed. However, when the United States entered World War II in late 1941, suddenly jobs became plentiful for women as men marched off to fight.

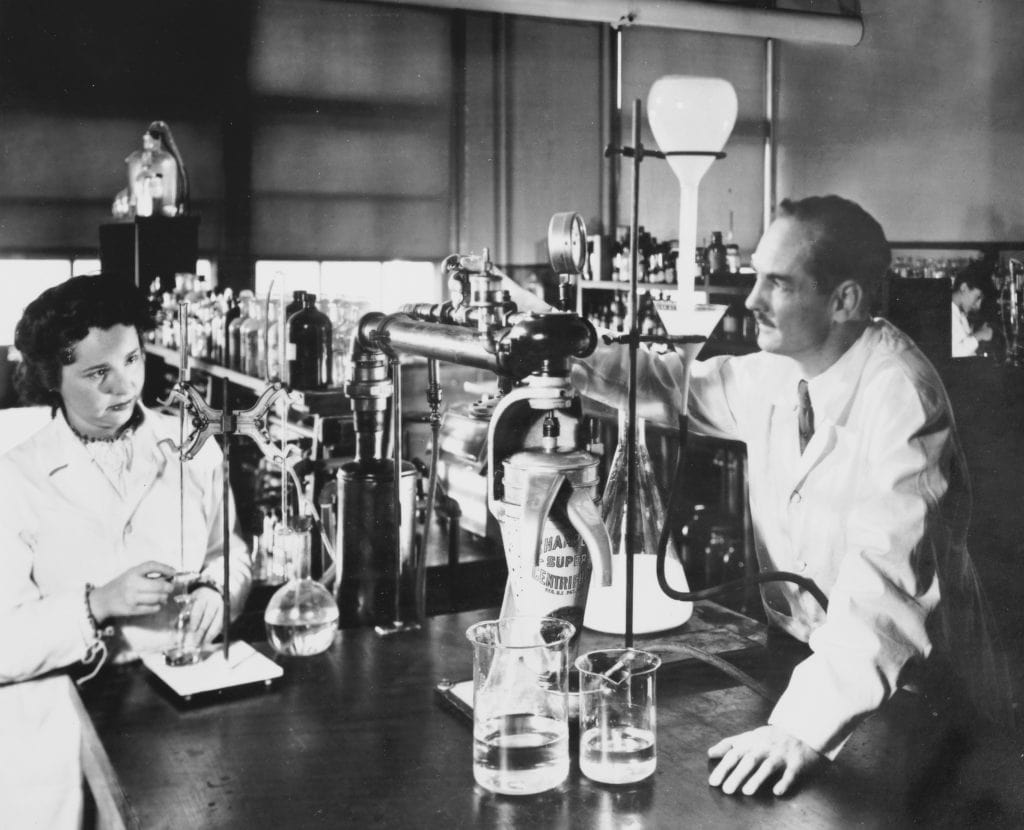

Elion’s life-transforming break came in 1944 when a laboratory assistant position opened at Burroughs-Wellcome, a pharmaceutical firm a few miles north of the city in Tuckahoe, New York. There, one Saturday morning, she interviewed with Dr. George Hitchings, the head and sole member of that firm’s biochemistry department. Hitchings hired Elion on the spot, thus launching an extraordinarily productive scientific partnership that would endure for 40 years. (You may have noticed that we have a Hitchings Avenue in Laureate Park that runs alongside The Gatherings complex.)

What so attracted Elion to Dr. Hitchings were his radically new ideas for designing drugs. Hitchings proposed to alter the chemical composition of the four building-block bases of the DNA molecule. These building blocks are the rungs of the corkscrew ladder that make up the DNA double helix. These rungs, or bases, are adenine and guanine (the purines) and cytosine and thymine (the pyrimidines). After analyzing the structures of these bases, Hitchings and Elion developed derivatives with chemical structures slightly different from the natural bases. Though the specific architecture of DNA was not described until the 1950s, it was already known that these four bases were essential components in the process of replicating cells. Hitchings and Elion called these imposter compounds “rubber donuts” because they looked like the real thing but could not be processed correctly by cells. The hope was that cancer cells would import these altered molecules in an attempt to support their growth efforts. Since the altered molecules were slightly different in structure, they did not support cell growth, and the cancer cells died.

Elion’s first success with this new “rational” approach for drug design came in the early 1950s with the development of mercaptopurine, which was shown to be an active agent against childhood leukemia. The first trials of this drug halted the progress of the disease for one or two years only, but later, versions of the drug proved to be increasingly effective. Eventually, through the use of mercaptopurine and analogous medications, the survival rates for childhood leukemia rose from 10% in the 1950s to over 90% today.

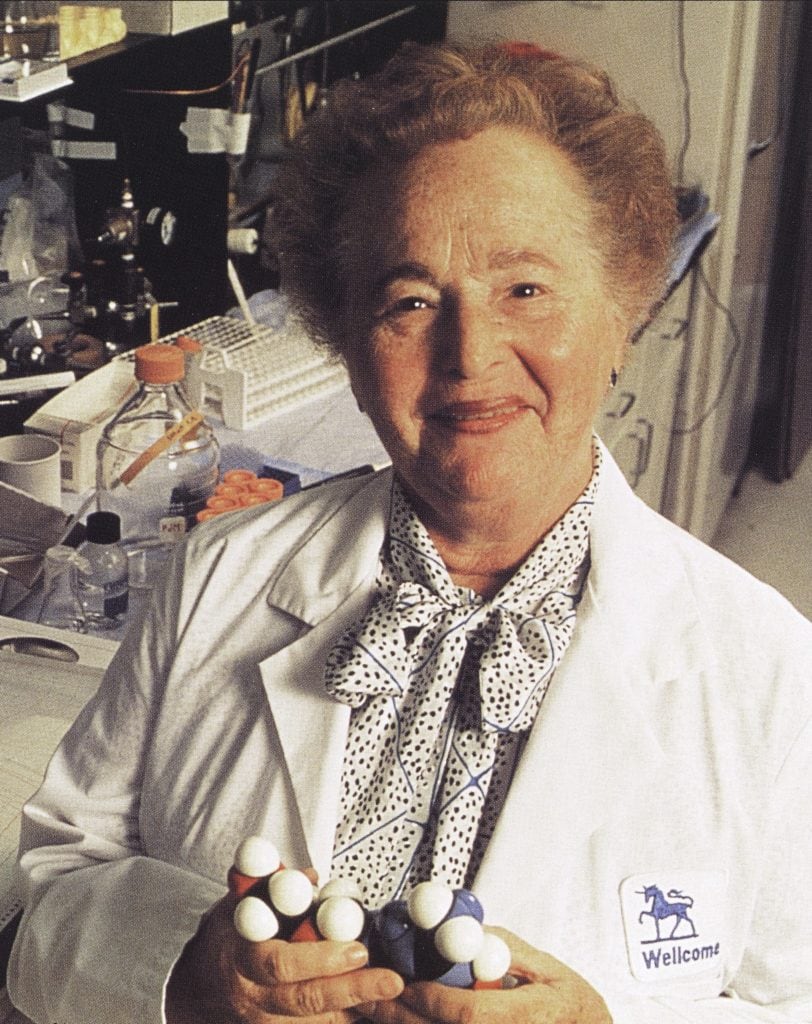

You would think that devising a cure for leukemia would be the crowning achievement of a scientist’s lifetime. But in the early 1950s, still in her 30s, Elion was just getting started. In the decades that followed, she developed an array of drugs to combat malaria, meningitis, sepsis, gout, and tissue rejection in organ transplants. In the 1960s, her attention shifted to viruses, a pursuit that produced acyclovir, the world’s first antiviral medication. If you have used acyclovir to treat cold sores, thank Gertrude Elion for the relief you obtained.

Having never married (her young fiancé died of a bacterial illness) or obtained a Ph.D. (opting instead to keep her job at Burroughs-Wellcome), Elion pressed on happily in her lab, offering our world a wealth of medications that have improved the health of millions. Her 1988 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, won together with George Hitchings and the Scottish physician Sir James Black, seemed an understatement for a woman who accomplished so much.

Elion Street winds an arc along the giraffe-shaped lake that laps against Canvas Restaurant. Were Elion alive today to visit the street that bears her name, she would likely linger at the point of that arc to gaze contently across the waters toward Nemours Children’s Hospital, where scores of children have found healing through the medicines she pursued or perfected throughout her life. Fantastically-modern, ingeniously-designed homes will soon rise at that spot, reflecting the raw creativity that she herself drew upon to design her life-saving medications. Surely, Laureate Park has found the ideal setting to honor Gertrude Elion, that exemplary model still today for so many aspiring young women of science.

Next month: Roger Martin du Gard, Gallic Wordsmith

Dennis Delehanty moved to Laureate Park with his wife, Elizabeth, from the Washington, D.C., area in mid-2018 and began to research and write about the Nobel laureates honored by the street names in our neighborhood early last year. You can contact Dennis at donnagha@gmail.com.