This is the tenth in a series of articles that celebrate the lives of the Nobel Prize laureates whose names grace the 125 streets of Laureate Park and the first to honor the life and work of a Latin American literary giant.

That sober date has arrived when we pause to review our lives over the past year, contemplate struggles won and lost, and seek ways to better ourselves in the weeks and months ahead. At this period of reflection, some of us may think upon our successes or misses as parents and providers, as we watch our toddlers so quickly tumble through time to turn into teenagers then leave for college, returning four years later as full-grown princes and princesses ready to go forth to accomplish great deeds. Seeing time slip by so speedily, we understand why some mothers often wish the clocks on the wall would slow down or even stop so that their toddlers would, well, keep toddling, maybe forever.

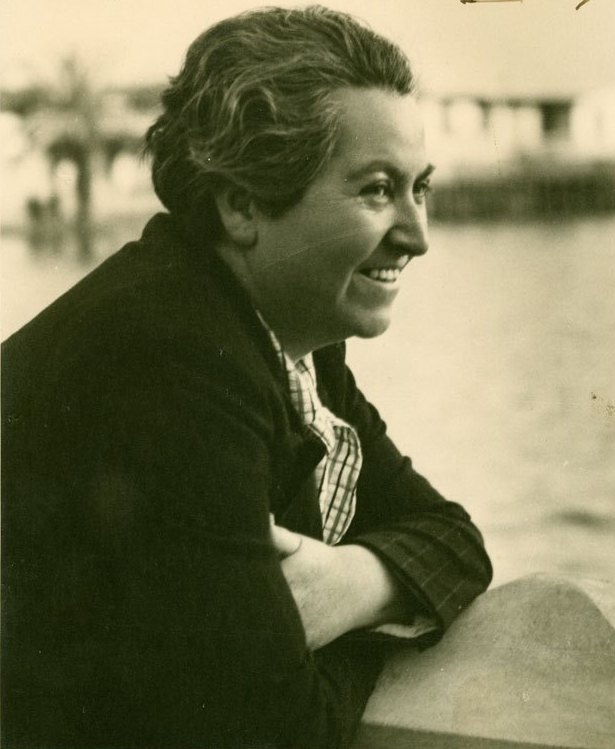

Our daily lives do present us with serious challenges. So much so, at times, that we may grouse that we have been dealt a hopeless hand. In those moments, we should step back and consider the life of Nobel laureate Gabriela Mistral, the Chilean poet, educator and diplomat, who overcame overwhelming obstacles in her early life and multiple difficulties in adulthood.

In 1889, in the northern reaches of Chile, a child named Lucila de María del Perpetuo Socorro Godoy Alcayaga entered this world, the offspring of a father of European stock and mother of Amerindian heritage. Professor Juan Godoy, an amateur poet himself, abandoned the family when Lucila turned three. Mom and the kids settled in the mountainous town of Montegrande, where the lush vineyards and wooded acres encircling the village enchanted Lucila, allaying her loneliness. But when Lucia reached sixth grade, the principal of the local primary school wrongfully accused her of stealing several sheets of paper, branding her as intellectually disabled (the term applied then was much harsher). Her classmates’ cruel taunts of “ladrona, ladrona,” marking her as a thief, echoed in Lucila’s ears as the principal announced her expulsion. Never again did she return to school as a student.

Instead, Lucila tutored herself. Still a teenager, she began to compose poetry, having discovered verses left behind by her father, and submitted her first poems, short stories and essays to local newspapers. These early writings gained the attention of local educators, who offered the 15-year-old a job as a teacher at a rural school, where some of her students were adults. Soon thereafter, Lucila adopted the pseudonym Gabriela Mistral, combining the names of two of her favorite poets – the Italian Gabriele d’Annunzio and, prophetically, that of Frédéric Mistral, the 1904 Nobel laureate in literature who championed the endangered language of Occitan of Southern France, Spain and Italy.

Tragedy pursued Gabriela as she entered adulthood as suicides claimed her first young love, then later a nephew she had adopted, never having given birth to children of her own. Gabriela poured her grief into poetry and produced verse of powerful beauty that both gained the admiration of her readers and won her the Chilean Juegos Florales [Floral Games] poetry award in 1914. By her mid-20s, Gabriela had become a celebrity in her home country, not just for her poetry but also for her innovative work as an educator, teaching in schools throughout Chile (and mentoring the budding teenage poet Pablo Neruda along the way), while rising in stature to become principal of the country’s premier girls’ high school in Santiago. In 1922, the Mexican Minister of Education, impressed by her teaching methods and her insistence that schooling should be accessible to children of all social classes, invited Gabriela to Mexico to reform that country’s educational system. This two-year assignment launched Gabriela’s career as an international advocate for universal education and human rights. In 1926, she accepted an appointment to represent Latin America in the newly created Institute for Intellectual Cooperation of the League of Nations in Paris. This move to Europe effectively imposed on Gabriela an itinerant life in exile, and for the rest of her life, she would return to her native country only twice on brief visits.

From 1932 onward, Gabriela served as Consul for Chile in Naples, Madrid, Lisbon, Nice, Petropolis (Brazil), Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, Veracruz, and New York City, and spoke repeatedly before the United Nations and the Organization of American States. Real recognition came to Gabriela in 1945 as she won the Nobel Prize in Literature, the first Latin American to be so honored. She remains to date one of only two female Latin American Nobel laureates.

In your New Year’s resolutions, you may have included plans to learn or improve your Spanish (several patrons at Canvas Restaurant, at least, have expressed to me these noble intentions). Orlandoans, of course, have many reasons to learn Spanish. Among these, though, could we add a desire to enjoy the original rhythmic rhymes of a towering Latin American poet such as Gabriela Mistral? Our neighborhood’s young mothers, for example, would instantly understand the deceptively deep emotion expressed in Gabriela’s collection of verse entitled Ternuna [Tenderness], where a string of poems speak of a mother’s boundless love for her children. In one poem, ¡Que no crezca! [Don’t grow up!], Gabriela writes the lines below, which are rendered into English only with difficulty.

Que el niño mío

así se me queda.

No mamó mi leche

para que creciera.

Un niño no es el roble,

Y no es la ceiba.

Los alamos, los pastos,

los otros, crezcan:

en malavisco

mi niño se queda.

[Let my child stay as he is/He never drank my milk so he should bigger be/A child is no elm, nor a ceiba tree/The poplars, the pastures, and the rest, may flourish and grow/but let my child remain a little marshmallow.]

This is a tiny fraction of Gabriela Mistral’s delightful verse about children. Her full collection of poems waits for you to explore.

Next month: Daniel Bovet, Champion of Curative Chemistry

Dennis Delehanty moved to Laureate Park with his wife, Elizabeth, from the Washington, D.C., area in mid-2018. Dennis completed a long career in international affairs at the U.S. Postal Service, the United Nations and the U.S. Department of State, jobs that required extensive global travel and the acquisition of foreign languages. You can contact Dennis at donnagha@gmail.com.