The Promoter of a Peace Pact That Could Not Prevent War

This is the second in a periodic series of articles that celebrate the lives of the Nobel Prize laureates whose names grace the 100 streets of Laureate Park. These laureates are extraordinary men and women – many of whom are alive today – who through their lifetime achievements have made our daily lives immeasurably richer, often in ways not readily evident. Through these articles we hope to introduce you to these exceptional individuals and encourage you, perhaps, to learn more about them.

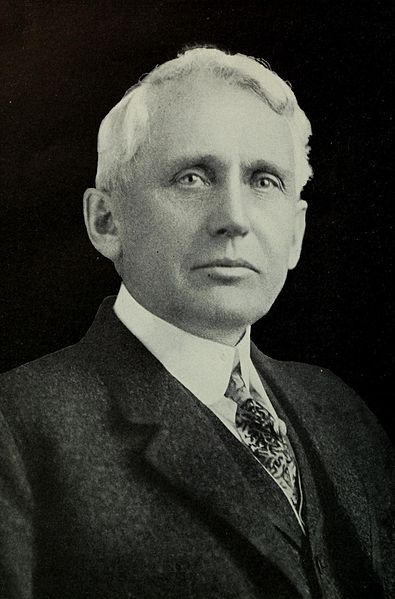

In Laureate Park is Kellogg Avenue, whose residents may be forgiven if they associate this name with Frosted Flakes, Special K or Battle Creek, Mich. Certainly, the family name “Kellogg” emerged from the food industry, at least its medieval version, having derived from a Middle English term for slaughtering (“Kellen”) hogs. But John Harvey Kellogg, designer of corn flakes, prolific inventor, and notorious eccentric, won no Nobel Prize. Rather, the Minnesotan trustbuster and diplomat Frank Billings Kellogg earned that honor in 1929, primarily for the Kellogg-Briand Pact, which optimistically outlawed war. More recently, of course, Frank B. was chosen for the equally singular distinction of bearing the name of a street in Lake Nona.

Perhaps most remarkable about Kellogg’s extraordinary life is that it began so humbly. Born a modest farm boy, Kellogg patched together only a desultory primary education in upstate New York before his family moved west to Minnesota. There, leaving the family farm as a teenager, and having clocked in a couple more years in public schools, Kellogg managed to land a job in a law firm as what we would now likely call a gopher. The appeal of the legal profession must have enchanted Kellogg, as he resolutely set about to study law on his own (as well as history, Latin, and German), passing the Minnesota state bar exam in his 30th year.

After entering his cousin’s law firm in 1887, Kellogg took on cases representing railroads as well as iron mining and steel manufacturing firms, earning considerable wealth in the process, while befriending such magnates of monopolies as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller. Surprisingly, despite his work in defense of these large, dominant companies, Kellogg gained national attention at the turn of the century as a trustbuster for his successful prosecution of the General Paper Company in defense of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, a case which President Theodore Roosevelt had invited him to undertake. Kellogg burnished his trustbuster reputation with subsequent prosecutorial victories over the Union Pacific Railroad and, poignantly, John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company.

Such achievements would already have made Kellogg a figure of national historical significance. But Kellogg’s outstanding career in politics and international diplomacy still lay ahead.

In 1904, Kellogg had begun his involvement in national Republican politics and by 1916 won election to the U.S. Senate from Minnesota. As his first official act as senator – supremely ironic in light of his later diplomatic work – Kellogg voted for U.S. entry into World War I. In the following decade, this conflict was seen as the “war to end all wars,” an objective Kellogg took to heart, working tirelessly throughout the 1920s to achieve some mechanism by which further such human cataclysms could be prevented. As a senator, Kellogg lobbied hard for U.S. ratification of the League of Nations, but that effort failed, as did Kellogg’s electoral bid to return to the Senate in 1922. Thus began Kellogg’s formal career as a diplomat, first as U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom, then as Secretary of State, serving under President Calvin Coolidge until 1929.

In 1927, Aristide Briand, Kellogg’s French counterpart (and also the bearer of a street name in Laureate Park), proposed a bilateral treaty that would denounce war between France and the United States. Wary at first of the proposal, Kellogg reconsidered and transformed Briand’s draft text into a full-blown multilateral convention, which by the end of the decade fully 62 nations had ratified. At the core of the treaty was the concept that signatory states shall promise not to use war to resolve “disputes or conflicts.” Critics of the pact decried the document’s moralistic bent, and from a more practical perspective, the pact failed within months to stop Japan’s incursion into Manchuria, the first real test of its efficacy.

Nevertheless, the Kellogg-Briand Pact, which remains in effect today, has had a major impact on international affairs since its promulgation nearly a century ago. The notion of renouncing war as an instrument of national policy finally took hold at the close of World War II, and that same concept became a founding principle of the United Nations. Prosecutors at the postwar Nuremberg trials turned to the pact to convict Nazi leaders as war criminals. Most importantly, many argue that the relative absence of major wars among major nation states since 1945 can be traced back to the work accomplished two decades earlier by Frank Billings Kellogg and Aristide Briand, and the pacifist legacy they bequeathed to humanity.

Dennis Delehanty moved to Laureate Park with his wife, Elizabeth, from the Washington, D.C., area in mid-2018. Dennis completed a long career in international affairs at the U.S. Postal Service, the United Nations and the U.S. Department of State, jobs that required extensive global travel and the acquisition of foreign languages. Please contact Dennis about the Laureate Park Nobel Prize honorees or suggestions for future articles at donnagha@gmail.com.