This is the eighth in a series of articles that celebrate the lives of the Nobel Prize laureates whose names grace the 125 streets of Laureate Park. These laureates are extraordinary men and women – many of whom are alive today – who through their lifetime achievements have made our daily lives immeasurably richer, often in ways not readily evident. Through these articles, we hope to introduce you to these exceptional individuals and encourage you to learn more about them.

As a young woman, Doris Lessing would certainly not have chosen to live on Lessing Avenue. Committed Communists are rarely attracted to neighborhoods such as Laureate Park but prefer rather to preach the coming revolution to the downtrodden masses inhabiting large cities.

Or at least who used to inhabit big cities. Times have changed. The raw fear of Communism that once loomed over the American psyche now seems silly, and Doris Lessing herself had already begun to turn away from that ideology as early as the 1950s. So, to portray the life of this giant of English literature through the lens of her generally leftist leanings would be more than unjust. This is a woman who, in a life spanning 94 years, produced no less than 60 important books, much of it fiction, on a vast range of subjects and characters, for an average of nearly one book per year over her writing career. Doris Lessing is a writer whom you approach with humility and awe.

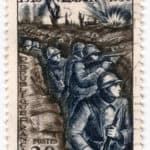

At age 88, as she stepped out of a taxi in front of her London home, journalists surrounded Doris to tell her the news that she had won the 2007 Nobel Prize for literature. What did the Nobel Prize mean to her, they inquired? A bit peevishly, she retorted, “Well, I’ve won all the prizes in Europe, every bloody one. So I’m delighted to win them all … it’s a royal flush.” If this YouTube scene were your only exposure to Doris Lessing, you might conclude that this was just some momentary venting of a cranky elderly lady. In audio and video interviews, though, Doris could command considerable charm when, for example, she would describe her enchanting early childhood in Persia, which sadly ended with her father Albert’s disastrous decision to move the family in the 1920s to raise maize in the remote bush of what was then Southern Rhodesia. Albert had lost his leg in World War I, had little agronomy experience, then contracted diabetes, all of which seriously complicated his life as a farmer, a life that Doris’ mother, Emily, who dreamed of returning to England, utterly detested. Meanwhile, Doris bickered constantly with her mother and dropped out of school at age 14. (Were any other Nobel laureates high school dropouts?) But Doris read constantly and, as a young adult, penned a novel, The Grass Is Singing, which, after a series of rejections, was published after she had left Africa for London to seek a better life. By then, Doris had already married and divorced twice and had borne a son and daughter.

Many consider The Grass Is Singing to be Doris’ finest achievement. This is a backwards mystery novel. On the first page, we learn the identity of both the victim – a “city girl” married relatively late in life to a failing bush farmer, much like Doris’ own mother – and the murderer, a native laborer who toiled as houseboy and cook in the family’s ramshackle tin farmhouse. We only begin to understand how this domestic tragedy could unfold in the following pages, as Lessing incisively depicts the sparse lives of white immigrants in the South African bush country and their precarious daily interactions with the native laborers whom they mercilessly exploit.

Another of Lessing’s notable novels is The Good Terrorist, a title that packs into three little words an abundance of contradiction, sarcasm and irony. In this story, we follow the adventures of Alice Mellings, a committed revolutionary, who helps her hapless fellow radicals to repair an abandoned and dilapidated “squat” house in London through theft, deception and considerable toil. Hardly any likable characters populate this novel, including Alice herself, who is part earth mother, tirelessly caring and cooking for her ungrateful and unhelpful housemates, and part neglected lover and amateur terrorist. But having helped her housemates to carry out a deadly London bombing, could Alice ever be considered “good?”

Readers interested in a sampling of Lessing’s further works could dip into The Fifth Child, where the arrival of a frighteningly misshapen, misanthropic child tears apart the previously happy life of an upper middle-class London family. Or Albert and Emily, in which Lessing imagines alternative biographies of her parents in which the two, in the absence of World War I, do not marry one another, but lead much luckier lives, entirely in Britain.

Many, though, consider The Golden Notebook as Lessing’s masterpiece. This is the book that caused Lessing’s ardent admirers to promote her as a leading feminist of the 1960s, a label she forcefully declined. For this work, Lessing invented an experimental format in which the various facets of the lives of her two female protagonists are recorded in four separate notebooks that only by page 583 combine into one “golden” notebook. Even enthusiastic readers should approach this ungainly, seemingly plotless novel with caution.

True, young Doris Lessing might not have preferred to live on Lessing Avenue. In her later years, though, she might have reconsidered, had she been able to visit her namesake street and appreciate its tropical architectural appeal. Some six years after her passing, Doris at least seems to project a curious pull over her would-be compatriots in our neighborhood, making her presence felt more deeply among us. How is this? Of the three British residents of Laureate Park I have met since moving last year to Laureate Park, two live on Lessing Avenue, and the third just moved to a new home just steps away on Sargent Street. Though living in close proximity, the three do not know one another – yet, anyway. A coincidence? Perhaps, though some say that there are no coincidences in life.

Next month: Toshihide Maskawa, the Diviner of Quarks

Dennis Delehanty moved to Laureate Park with his wife, Elizabeth, from the Washington, D.C., area in mid-2018. Dennis completed a long career in international affairs at the U.S. Postal Service, the United Nations, and the U.S. Department of State, jobs that required extensive global travel and the acquisition of foreign languages. You can contact Dennis at donnagha@gmail.com.