Humans get Lyme disease after being bitten by an infected blacklegged tick, and the number of infections is increasing nationwide. A College of Medicine researcher just earned a $2.2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to understand how this disease is able to escape our body’s immune system.

Humans get Lyme disease after being bitten by an infected blacklegged tick, and the number of infections is increasing nationwide. A College of Medicine researcher just earned a $2.2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to understand how this disease is able to escape our body’s immune system.

Her work is important because a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control says vector-borne diseases – those transmitted from insects like mosquitoes and ticks – are on the rise in the United States. Lyme disease accounted for 82 percent of reported cases of tick-borne diseases between 2004 and 2016. While the disease is most prevalent in the Northeast and rare in Florida, many of us travel to areas where Lyme disease is common and we can return home with the infection.

One of the challenges in treating Lyme disease is that some of its symptoms – including fever, headache and fatigue – can be mistaken for symptoms of other conditions. So, treatment with antibiotics can be delayed or missed. The infection can then spread to joints, the heart, and the nervous system, causing long-lasting damage.

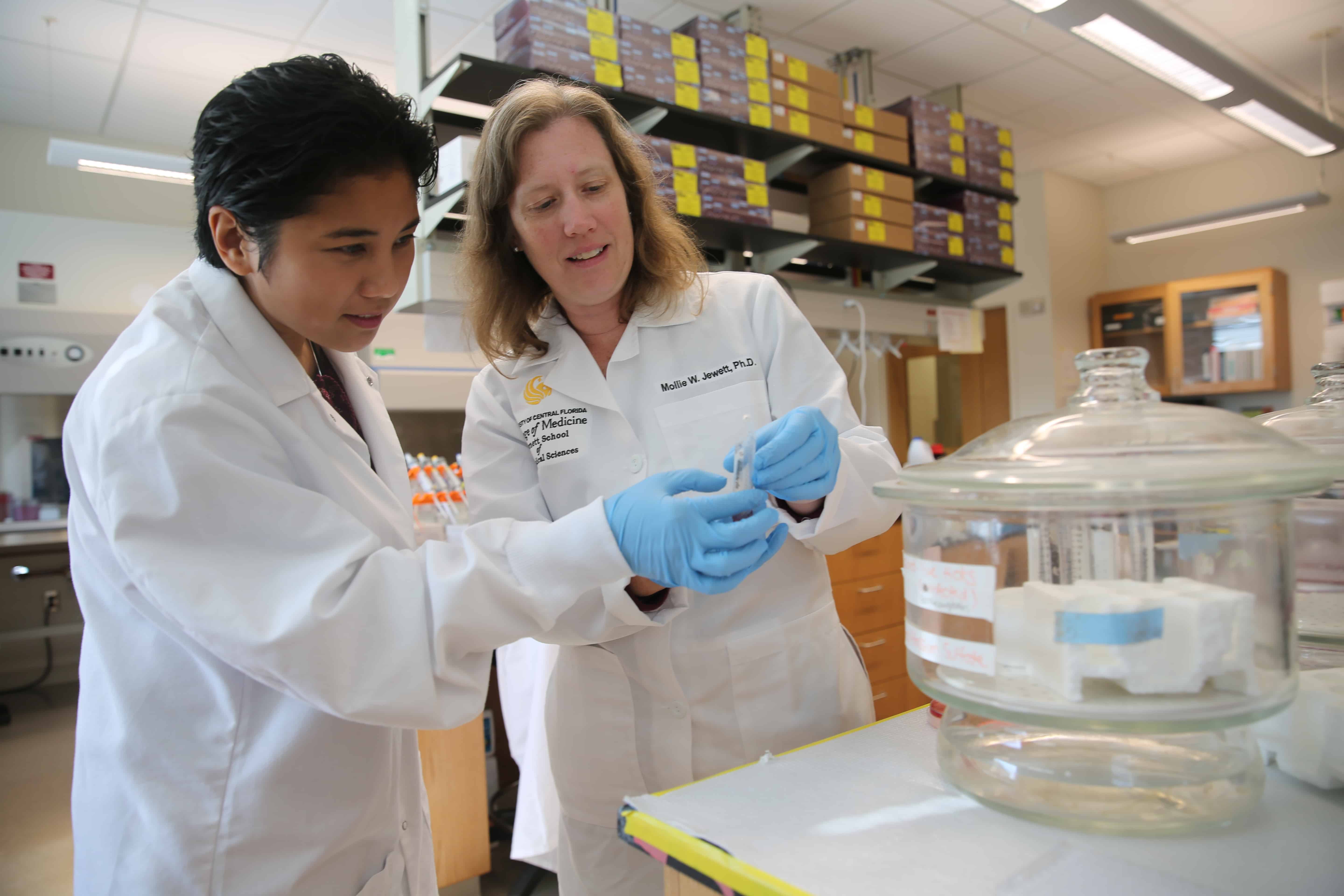

Dr. Mollie Jewett, who leads our Division of Immunity and Pathogenesis Research at the Burnett School of Biomedical Sciences, focuses her research on earlier detection and better treatments for Lyme disease. Her latest grant is a five-year competitive renewal of an RO1 or Research Project Grant she received in 2013. These grants are highly competitive – only about 12 percent of applications are funded – and are designed to support innovative health research by a sole investigator who addresses a public health need.

The bacterium that causes Lyme disease is transmitted by the tick at a single bite site. But for a person to acquire the disease, the infection must move quickly through the blood to the joints, heart and brain. Dr. Jewett and her team are looking at how the genetic makeup of the bacterium allows it to escape the immune system.

The bacterium that causes Lyme disease is transmitted by the tick at a single bite site. But for a person to acquire the disease, the infection must move quickly through the blood to the joints, heart and brain. Dr. Jewett and her team are looking at how the genetic makeup of the bacterium allows it to escape the immune system.

Dr. Jewett is collaborating with Dr. Shibu Yooseph, UCF professor of computer science and genomics and bioinformatics, and Dr. Justine Tigno-Aranjuez, an assistant professor in the Immunity and Pathogenesis Research Division.

“To disseminate, the bacteria has to overcome all these barriers that the immune system puts up,” Dr. Jewett explained. “So if we can figure out a way to strengthen the immune response or target the bacteria to make it more susceptible to the immune defenses, then we might even be able to prevent the infection from happening in the first place.”

Deborah German, M.D. is the Vice President for Medical Affairs and Founding Dean of the UCF College of Medicine. To learn more, visit med.ucf.edu.