Psst! It doesn’t necessarily involve talking.

There is no doubt that we, as humans, have developed the unique ability to use our voice for complex communication. Humans have a complete linguistic package. However, if you notice, we also use lots of nonverbal communication. If I go to a store and take the time to look at a clerk without speaking to him, I could probably get an instant read into what that person is thinking about or feeling at the moment. Are they bored, friendly, indifferent, sad, mad, etc.? Many times, you can tell just by studying that person, without having to utter a single world.

Now, picture a dog whose lineage has been shaped and molded over, some say, 15,000-20,000 years. They have learned to watch and study us all day long. Seemingly, they can read our minds. They seem to know the distinction of when it is time for the actual walk and not just when you’re going out to check the mail. They seem to know when it is time for dinner or when they will take a ride in the car. But I assure you, they cannot read our minds; instead, they have been able to study us long enough that any micro movement we make cues to a predictable event.

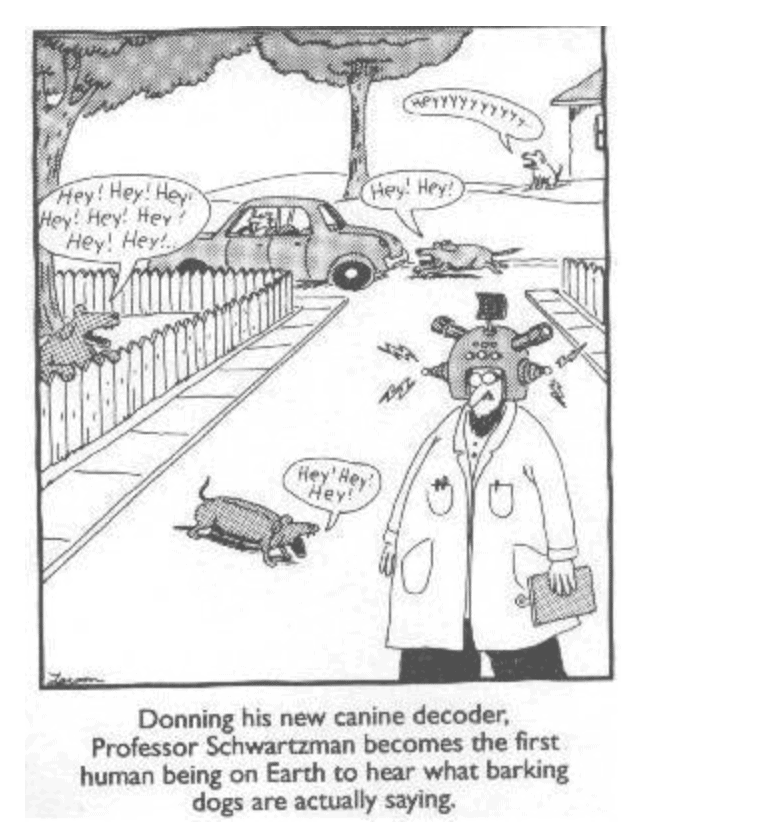

Because of this, we humans tend to get confused. Since they have studied our micro-cues, it is easy to think that we can use spoken language and they completely understand. I was in the Lake Nona Ace Hardware one time, and I noticed a fellow perusing the store with a huge and friendly German Shepherd. We were waiting in the check-out aisle, where there was a display of canine impulse sale items. Humorously, I heard the gentleman ask his dog, “Cooper, would you like one of these? How about this one? What about this Kong?” I assure you that the only thing the dog heard was his tone of voice but not the meaning of his words. We, including me, all speak to our canine companions for various reasons. And I think that most people have the innate understanding that our words do not carry meaning other than the verbal cues that have been taught. However, I have come across more than a couple of clients who were sure their dogs were assimilating more spoken language acquired outside of training.

As a trainer who has visited puppy clients’ homes many times per week, I often see the owner tell the dog to sit without any training whatsoever. The puppy invariably will look back at his human with confusion. The owner then says, “SIT!” even louder or “Sit, Rover, sit. Sit … Rover, sit.” Eventually, what happens is that the dog sits not because she understands the word but because she is merely waiting for something that makes sense. I am often told by the client, “Well, the dog knows to sit some of the time.”

This is why I advocate that a person with a new dog or puppy trains them using nonverbal communication first. In a sense, we show them what to do and then add a verbal cue later. It is a much more efficient and predictable way of training.

The danger of adding a cue before the behavior is taught is that the dog learns something other than the intended cue or the dog gets confused. This leads to inconsistent behavior prompting comments like, “Rover knows how to sit some of the time.” We also want Rover to know that “sit” is the cue and not “Sit, Rover, sit. Sit … Rover, sit.”

Here are some examples of training using nonverbal communication. Note: These are simple explanations of how dogs learn in a communicatively silent way, but there is no substitute for having the guidance of a qualified, positive, force-free trainer to help you through training.

Sit: Take a treat. Lure over the head, and as the dog looks up at the treat, she will eventually sit. Do this about 25 times, and when the routine is quick and snappy, add the verbal cue.

Down: From a sit, lower a treat from the dog’s nose along their breastbone to the floor. The dog will naturally want to look down at the treat and will lay down to get it. Likewise, do this about 25 times, and when the routine is quick and snappy, add the verbal cue.

Leash walking: Walk with your dog in a non-distracting environment and allow the dog to get rewarded for being right beside you. Hold a treat by your knee (or ankle, depending on the size of your dog) and make sure the dog only gets the treat in that “zone,” habituating the dog to always walk by your leg. Once the dog masters leash walking in a non-distracting environment, take it outside where there are more distractions. Not a word has to be uttered at all during training.

Stay: If your dog already knows sit, cue sit. Without saying a word, step backward by a foot or two. If the dog doesn’t move, give him a treat. Add the verbal cue after about 25 successful nonverbal stays. This is a way of teaching a dog to sit and stay until released, which would be helpful if you have a dog that tends to dash out the door.

Potty training: Reward heavily for the dog going potty on the grass, but say nothing and do nothing if the puppy goes inside the house. Over time, the dog will realize that going outside is much more rewarding. Yelling, scolding, and screaming at the dog for accidents will only cause the dog to go in a hidden corner of your house.

In all these instances, treats are methodically phased out as behaviors are mastered.

These are just some examples of where nonverbal communication with a dog is optimal in getting behaviors to happen quickly, reliably, and permanently if you rehearse them long enough. Moreover, the dog never has to be punished, physically molded, or kept guessing as to what you want from her.